Married Life

An Autobiography

Courtship & Marriage

“You can’t blame gravity for falling in love” Albert Einstein

It was the last day of November 1963 in the quiet town of Massena, New York, where a modest family wedding marked the beginning of a lifelong journey. The groom was Airman First Class Charles Tyrrell, stationed at Plattsburgh Air Force Base. The bride, Arlene Hart, hailed from Massena and worked in Rouses Point, a small town nestled about sixty miles north of Plattsburgh.

It was the last day of November 1963 in the quiet town of Massena, New York, where a modest family wedding marked the beginning of a lifelong journey. The groom was Airman First Class Charles Tyrrell, stationed at Plattsburgh Air Force Base. The bride, Arlene Hart, hailed from Massena and worked in Rouses Point, a small town nestled about sixty miles north of Plattsburgh.

And so began the story of our married life—a tale woven with the familiar threads of courtship, military service, shared dreams, and the unpredictable rhythm of civilian adventures. What followed was a rollercoaster of devotion and discovery, shaped by duty, ambition, and the ever-changing landscape of love.

Arlene and I first met in 1961 at Brodies nightclub, where I had earned a bit of local fame for my dancing skills—and proudly held the title of Limbo Champion. She was working as a supermarket cashier in Rouses Point and renting a room from a sweet elderly lady who, over time, became like a grandmother to us during our courtship.

Weekends were often spent at her parents’ home in Massena. Since it was a two-hour drive from Plattsburgh, I arranged to work the midnight shift at the base. That way, we could leave early Saturday morning after my shift and not return until Monday night—stretching our time together as much as possible.

Winter in upstate New York, though, was relentless. Snowbanks towered ten feet high, and many nights we braved blinding snowstorms on our way back to Plattsburgh. I remember driving on the side of the road with a window rolled down, using mailboxes poking out of the snowbanks as guideposts.

One night, the road ahead was completely blocked by a massive snow drift. I suggested we turn back and stay at a motel near Malone, but Arlene insisted we check with the ranger station to see when the road might clear. That night, I learned the value of the phrase “Yes, dear.”

We ended up at the New York State Trooper’s office, where I walked in looking like the Abominable Snowman—knee-deep in snow, topcoat on, no boots, and covered head to toe in powdery snow. Their expressions said it all. As expected, they had no idea when the road would be cleared.

So we returned to the motel, warmed up with coffee, and waited for the snowblower to come through. That night, I didn’t just learn the importance of compromise—I learned patience, too.

One winter evening, on our way home from Massena, Arlene suggested a “shortcut.” I trusted her instinct, but it didn’t take long to realize we were lost—and not just lost, but accidentally driving into Canada. It was a dramatic detour, to say the least.

A car began trailing us, and given the circumstances, I assumed it was border patrol. With ten-foot snowbanks lining the road, there was nowhere to turn around until we spotted a farmer’s driveway, freshly plowed and leading to his barn. As we passed the trailing car, my suspicion was confirmed—it was border patrol.

As we rejoined reaching the main road, sirens erupted and flashing lights lit up the snowy night. The officers weren’t exactly kind. Maybe I had interrupted their coffee and doughnuts! They searched our 1958 Chevy with intensity, even pulling out the back seat and tossing it into a snowbank.

Shortly after our engagement, while planning the wedding, Arlene came down with mononucleosis. She stayed with her parents to recover, which delayed the wedding and left me with the task of apartment hunting—a frustrating and often disheartening experience.

In the Air Force, living off-base came with a “subsistence allowance” meant to cover food and shelter. But local landlords seemed to treat it as a flat rent budget, offering places that were barely livable.

One apartment I visited had a plastic shower curtain hanging on the living room wall. As I turned to enter the bedroom, I discovered a gaping hole between the living room and bedroom. And the rent? Exactly the full subsistence allowance. It was clear that finding a decent place would be no small feat.

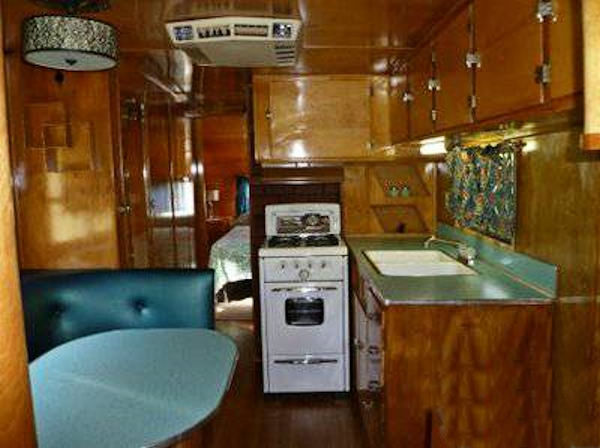

Then one day, I stumbled upon a hidden gem—a charming Spartan mobile home with an 8-by-16-foot attached cabana. It had a white picket fence out front and a tree in the side yard that gave it a touch of storybook serenity.

Inside, the place was immaculate. Shiny wood paneling gleamed throughout, and not a single stain or speck of dust could be found—even the water heater tucked beneath the kitchen counter looked freshly polished.

Inside, the place was immaculate. Shiny wood paneling gleamed throughout, and not a single stain or speck of dust could be found—even the water heater tucked beneath the kitchen counter looked freshly polished.

The little home came fully furnished. The living room featured a cozy sofa and a picture window dressed in flowered drapes. The kitchen was compact but efficient, with a snug dining booth that invited quiet breakfasts and evening chats. There were two bedrooms: one in the front with a double bed, and one in the back with twin beds. The mattresses looked nearly new—clean, firm, and ready for a fresh start.

The trailer park itself was small and well-kept, managed by a kind elderly couple who lived on-site. It was nestled in the quiet town of Peru, New York, just a short drive from the base. Most of the residents were military families, which gave the place a sense of camaraderie and shared purpose. It felt perfect to me. Still, I hesitated. The home was for sale, and I worried about Arlene’s reaction—the stigma of “trailer park living” wasn’t easy to shake.

But the practical advantages were undeniable. We wouldn’t need to buy furniture. The master bedroom had a spacious closet, and the second bedroom featured two closets separated by a built-in dressing table. The bathroom, though compact, had a tiled tub and shower. You could practically brush your teeth while sitting on the toilet—but it was clean, functional, and charming in its own way.

I was so excited about the find that Arlene’s parents offered to help with the purchase—on the condition that we scale back the wedding. It was a sensible trade-off, but convincing Arlene wasn’t guaranteed. She hadn’t seen the rundown apartments I’d toured, the ones with plastic shower curtains hiding gaping holes in the walls. I painted the picture as vividly as I could, and thankfully, it worked. She agreed.

I don’t remember much about the wedding day—not because I was drunk, but because I was nervous, scared, and overwhelmed. The timing didn’t help. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated just eight days earlier, casting a somber shadow over the entire country. Even at our reception, amid the congratulations and clinking glasses, every table buzzed with talk of JFK and the looming November blizzard.

By the end of the evening, the storm arrived in full force. We had planned to honeymoon in Lake Placid, a charming ski town nestled in the Adirondacks. But as we pulled away from the reception, the roads told a different story—cars stranded in medians and ditches, headlights dimmed by swirling snow. Reaching the mountains was out of the question.

Instead, we spent the night at a nearby motel. The next morning, it was nearly noon before the roads were passable. We made a quiet decision: skip the honeymoon and just “go home.” I was eager for Arlene to see the little home I’d found—the Spartan trailer with its flowered curtains and cozy charm.

But by the time we reached Peru, night had fallen, and my excitement quickly turned to heartbreak. The blizzard had knocked out the electricity. The home I had been so proud of was dark, silent, and freezing. I scrambled to get the furnace working while Arlene sat in the cold, staring at the flowered curtains and quietly crying.

The honeymoon was over before it began.

Winters in northern New York are not for the faint of heart. From December through February, temperatures routinely plunged to -20°F or lower. Life in our little community revolved around survival and routine: shoveling snow, chipping away ice, wrapping pipes with heat-tape to prevent freezing, and coaxing reluctant engines to start after days of sub-zero cold. It was a season that tested patience and perseverance.

But with spring came a quiet transformation. Arlene began to see the charm in our modest home. One morning, colorful crocuses bloomed unexpectedly along the white picket fence—a cheerful surprise that softened the memory of our blizzard-struck honeymoon. Arlene planted Lilies of the Valley around the tree in the yard, and together we furnished the cabana, turning it into a sunny retreat for warmer days. The space felt alive, and so did we.

Summer passed in a blur of beach trips to Lake Champlain and quiet evenings at home. We settled in, and Arlene made a heartfelt decision: she wanted to be a mother, not a working woman. Two weeks before Thanksgiving, our first son, Robert, was born. The mobile home, snug and familiar, kept us warm through another Plattsburgh winter. I even installed an automatic washer in the kitchen to ease the burden of diaper duty—a small gesture that made a big difference.

I found genuine satisfaction in military life. The structure, the responsibility, the sense of purpose—it suited me. I even considered applying for officer training and making a career of it. But Arlene’s dislike for military life ran deep. One Sunday, I was called out of church—right from the pulpit—for an emergency on the flight line. Arlene, cradling our baby, was mortified to leave mid-service. I understood her discomfort, but we were on a military base, and everyone understood the demands of duty.

Ultimately, we chose civilian life. My enlistment ended in August, and we agreed to move forward together. Arlene didn’t want to relocate to Ohio, so I focused my job search on companies in New York and Pennsylvania, hoping to find a role that honored my experience while keeping us close to familiar ground.

When interview time came, Arlene’s brother Keith joined me for the journey. We traveled from IBM in Binghamton, New York, to American Electronic Labs (AEL) in Lansdale, Pennsylvania. The interview at AEL felt like striking gold. They had a military contract to install ALT-7 ECM transmitters in armored personnel carriers—but admitted they didn’t know how to activate them. I’d spent three years working with ALT-7s and considered myself an expert. For once, my military experience wasn’t just relevant—it was essential.

AEL was impressed and extended what felt like a fantastic job offer. Lansdale, just outside Philadelphia, seemed like an ideal place to raise a family. I accepted the position and was set to begin in September 1965.

While I rented an apartment in Lansdale, Arlene stayed behind in Peru to sell the trailer. When it didn’t sell, we moved it to her parents’ property, where it eventually sold as a “cabin in the woods.” Arlene cried when it sold—perhaps because she was pregnant with our second child, or perhaps because that little home had become a symbol of our early years together.

Meanwhile, I found a lovely apartment in Telford, a quiet town near Lansdale. It was on the second floor of a large house at the corner of Penn Avenue and School Lane. The apartment had two bedrooms and a spacious eat-in kitchen, and even a detached garage for our trusty ’59 Chevy. The house belonged to a friendly young couple with preschool children, and the neighborhood was ideal. We could walk to the grocery store, the bank, and the train station—everything we needed was close at hand.

In February 1966, our second son, Joseph, was born at Lansdale Hospital. Life was beginning to take shape again—new job, new town, growing family. It was a season of quiet promise.

Settled Down

“Arlene's parents came for Thanksgiving and stayed until April”

My job at AEL had proven to be a rewarding chapter. The skills I’d honed in the Air Force translated seamlessly into the civilian world, and my expertise with ALT-7 ECM transmitters quickly became indispensable. Business trips took me across the country—from California to Arizona—and even overseas to Italy, where I found myself navigating both technical challenges and cultural surprises.

My job at AEL had proven to be a rewarding chapter. The skills I’d honed in the Air Force translated seamlessly into the civilian world, and my expertise with ALT-7 ECM transmitters quickly became indispensable. Business trips took me across the country—from California to Arizona—and even overseas to Italy, where I found myself navigating both technical challenges and cultural surprises.

With professional stability and a growing family, Arlene and I began to consider buying a house of our own. The apartment in Telford had served us well, but we were ready for something permanent—something that felt like ours. We wanted space for the boys to grow, a yard to play in, and a place where we could plant roots.

While house hunting, we came across a beautiful stone-front home. The builder was Joe Pascal & Sons and he was developing a small community of ten homes along Moyer Road, an area surrounded by peaceful Mennonite farmland. His standard design included three bedrooms, a full basement, and a one-car garage. And I was immediately impressed by the craftsmanship.

Around 1967 or 68, we took a meaningful step forward to build the home. The location was in Franconia Township, just west of Telford and Souderton, Pennsylvania, a quiet, open, and secluded area, perfectly suited for our growing family. When we learned construction hadn’t yet begun, we had the rare opportunity to choose any lot on the road. We selected one adjacent to a right-of-way, offering a bit more breathing room and flexibility.

The base price of the house was $19,000, but we opted for several upgrades: a fireplace, a formal dining room, and a heated basement. The fireplace was standard, but the builder warned that his oil heating system couldn’t extend to the basement. He also cautioned that closing off the dining area from the kitchen for a formal room would make it too dark.

I did some research and found a solution. The electric company was promoting “all-electric homes,” and electric baseboard heating offered individual thermostats for each room—including the basement. To solve the lighting issue, we could replace the dining room window with sliding glass doors, which would flood the space with natural light.

The builder approved our modifications, but when we applied for the loan, we hit a snag: building a home required a 20% down payment. Arlene’s parents generously lent us $2,000 to cover the difference, and we moved forward. Interestingly, our electric heating and formal dining room design were options later adopted by the builder in future homes.

Our new home qualified as a “Medallion Home,” a designation for all-electric residences. Electricity cost just one cent per kilowatt hour, and the basement stayed pleasantly warm all winter. The dining room was bright and inviting, though we eventually realized we’d need to build a deck to make use of those sliding glass doors.

With an acre of land, the builder had only sodded the front yard and scattered some grass seed about a hundred feet behind the house. But I had a broader vision. I wanted to seed the entire backyard, and Arlene dreamed of a large garden. So I invested in a 10-horsepower Allis Chalmers tractor, equipped with a 42-inch mower, a 34-inch roto-tiller, and a 36-inch dozer blade.

With an acre of land, the builder had only sodded the front yard and scattered some grass seed about a hundred feet behind the house. But I had a broader vision. I wanted to seed the entire backyard, and Arlene dreamed of a large garden. So I invested in a 10-horsepower Allis Chalmers tractor, equipped with a 42-inch mower, a 34-inch roto-tiller, and a 36-inch dozer blade.

The dozer blade proved essential for spreading the topsoil needed to seed the yard properly. With the tiller, I carved out a generous garden plot where we grew corn, tomatoes, onions, beans, broccoli, cucumbers, and even pumpkins. Once the grass filled in across the acre, the mower became a trusted companion—turning weekend chores into moments of quiet satisfaction.

Most weekends were spent tilling and mowing, but Sunday evenings brought a different rhythm. After a hearty meal of meat, potatoes, and fresh vegetables from our garden, I’d sit back and admire the lawn, watching the sun dip below the fields. In those moments, every ounce of effort felt worthwhile.

Arlene embraced her role as a stay-at-home mom and found joy in cooking. Through canning our vegetables, the garden fed us well into the winter months. Meanwhile, I worked full-time as an electronic technician at American Electronic Labs and attended LaSalle University at night to pursue an engineering degree. LaSalle didn’t accept my math credits from the University of Cincinnati, but they did accept my history credits from Plattsburgh State—a small victory in a long balancing act.

That first Christmas in our new home brought an unexpected memory. While searching for a tree, the boys gathered pine cones, which we placed in a bowl as a holiday centerpiece for the dining room table. After a few days, we heard faint crackling sounds—the pine cones were opening, releasing tiny seeds.

Inspired, we planted the seeds in egg cartons, the way we had started plants for our garden. Soon, delicate sprouts emerged, each resembling a single pine needle. Once they grew into seedlings, we transplanted them to a protected spot outside. In time, two lovely little pine trees stood as living reminders of that winter—symbols of growth, patience, and the quiet magic of family life.

By the time we repaid the loan from Arlene’s parents, life had begun to feel stable again. But tragedy was quietly approaching. Her parents visited us for Thanksgiving, and during their stay, we learned that her mother, Beatrice—known lovingly as Betty—had cancer. When we discovered she was expected to travel from Massena to Buffalo for radiation treatments, we insisted they stay with us and receive care at Abington Hospital, just 25 miles away.

With the added household expenses, Arlene took a part-time job operating a printing press for a Telford company that produced diplomas and graduation rings. By April, though, Betty had grown weary and homesick. They returned to Massena, and just a few months later, she passed away. She was deeply loved, and her funeral was a heartbreaking farewell.

But grief was compounded by betrayal. After the funeral, Arlene’s father, Arile, opened the family safe expecting to find the U.S. Treasury Bonds he’d purchased faithfully since his service in WWII. Instead, he found stacks of empty envelopes. Betty had quietly cashed them all.

The man who had built two of their homes with his own hands was left with nothing. His brother, who lived nearby, took him in, and his youngest son Gary took over the house. It would take years before I fully grasped the meaning behind the old saying: “like mother, like daughter.”

At American Electronic Labs, I earned a decent salary, but our aging 1959 Chevrolet Impala—bought from Arlene’s cousin—was showing its age. The rocker panels had rusted out, so I masked them with tape and spray-painted them to match the car, just to pass Pennsylvania’s annual inspection.

Work at AEL kept me traveling, which Arlene resented. My night classes at LaSalle University for an engineering degree added to the strain. Finances were tight, and I needed a raise. But President Nixon’s wage freeze and the end of government contracts left engineering jobs scarce.

Then I spotted a quirky classified ad for a management role. I responded with a resume and cover letter that mimicked the ad’s playful tone. Months passed with no reply, and I chalked it up as a failed experiment—until one Sunday, while painting the house trim, I got a call from S&S Associates.

The caller was impressed that I’d written the resume and cover letter myself and asked if I could come to his office in King of Prussia immediately. I was in work clothes, but he insisted: “Come as you are.” I cleaned up and went. Sy Hochman hired me that day, offering a very generous salary.

Though the commute was long, the position at S&S Associates allowed me to retire the Impala and buy a used 1967 Oldsmobile. Over the next two years, the business grew from one employee to sixteen. I was named CEO of Service in Electronics, earning nearly double the median income of the time. I felt prosperous. I no longer traveled for work. We had a lovely home, and I eventually traded the Oldsmobile for a brand-new 1972 Chevrolet Impala.

But Arlene remained unhappy, and life was about to take a tragic turn. Sy Hochman—my boss, friend, and mentor—died in an accident while on business in North Jersey. His partners in Bethesda, Maryland, shut down Service in Electronics. Just like that, I was unemployed.

I sent out resume after resume with no response. Eventually, I accepted a position in the industrial x-ray business from a former associate. Then, to my surprise and relief, I received a reply from JCPenney regarding a resume I had submitted months earlier for a product service manager role.

The interview went well. They valued my experience and leadership, and offered me the opportunity to establish and manage a new product service center in Dayton, Ohio.

Trouble Brewing

“The saddest thing about falling in love is that sooner or later something will go wrong”

Service in Electronics had become the largest home electronics repair service in the Delaware Valley under my leadership. This was the type of intuitive leadership that JCPenney sought for managing a product service center.

Service in Electronics had become the largest home electronics repair service in the Delaware Valley under my leadership. This was the type of intuitive leadership that JCPenney sought for managing a product service center.

JCPenney service centers were independent operations that provided repair and maintenance for home electronics, appliances, and gas engine products sold in their full-line stores. The manager was accountable for the entire operation, including profitability.

After six months of training, JCPenney presented me with the chance to launch a new Product Service Center in Dayton, Ohio. I traveled to Dayton ahead of my family to set up the operation and search for housing. My search focused on Centerville, Ohio near the JCPenney store in the Centerville Mall.

I dedicated most of my time to setting up the service center, transforming an empty warehouse into a well-organized and efficient repair facility. When Arlene joined me, we found a brand new two-story colonial home in Centerville. With four bedrooms, two bathrooms, a spacious front porch, and a two-car garage, it was a significant upgrade from our small ranch house in Franconia.

Our furniture went perfectly to bring warmth and character to the family room and we bought all new furnishings to adorn the dining room and living room in a rich Spanish decor.

The formal dining room was anchored by a stately Spanish Pine set, its table comfortably seating eight guests, including two captain’s chairs that added a touch of distinction. The elegant hutch gleamed with crystal stemware and two complete sets of Mikasa china, while the matching server displayed crystal candlesticks and an ornate china fruit bowl—a centerpiece that seemed to glow in the soft evening light.

The master bedroom held a quiet grandeur, but it was the bathroom that truly stood apart—unlike any I had seen before. To the right as you entered, a long counter stretched across the wall, featuring dual sinks, matching cabinets, and a full-wall mirror framed by decorative lighting. Behind that wall, cleverly concealed, were the shower and toilet—each accessible from opposite ends, offering both privacy and architectural intrigue. Directly across from the sinks stood two spacious walk-in closets, a testament to thoughtful design and everyday luxury.

Centerville was a distinguished and welcoming community, known for its shopping mall and quiet elegance. Though our property measured just half an acre, it offered more than enough space for a thriving vegetable garden—a small but meaningful source of pride.

Our neighbors included lawyers, physicians, and senior managers from Dayton’s leading corporations: NCR, IBM, GM, Frigidaire, and Delco. While our home wasn’t the largest in the community, it was filled with warmth and purpose. Both of my sons, Bob and Joe, had their own bedrooms—a simple luxury that gave them space to grow.

The progressive school system proved to be a perfect fit for both boys. Bob flourished in a collaborative learning environment, where students worked together and teachers served as guides rather than taskmasters. Joe, always eager to improve, advanced two grade levels in reading. That summer, he set his sights on winning a prize for reading the most books—and he did, with determination and joy.

Outside the classroom, Bob and Joe were active and industrious. They played Little League baseball and soccer, and both took on newspaper routes. Ever resourceful, they often combined their deliveries, stacking papers in their wagon to cover more ground together. To support their efforts, I bought them a used JCPenney minibike. They rode it proudly, towing the wagon-load of papers behind them like a pair of young entrepreneurs on a mission.

Centerville was also a place where fathers could only attend their children’s baseball and soccer games when they weren’t traveling for work. I didn’t travel, so I was usually there, cheering from the sidelines. But one day I arrived late. I didn’t think much of it until I learned, much later, that Arlene had told Bob and Joe, “He loves his job more than he loves you.” The words stung—not because they were true, but because they were so far from it.

I was successful, yes, but never at the expense of my family. I had employees who handled emergency service calls, and when they worked late, I worked late. They relied on me and I believed in leadership by example. Still, in hindsight, I wonder if I was too focused on responsibility to notice the quiet unraveling at home.

In the fall of 1974, I purchased a new Chevrolet Monza—a sleek, compact V8 that suited my daily commute perfectly. Arlene, however, was furious. She dismissed it as “a sports car” and refused to ride in it. Symbolically, perhaps, it was a modest indulgence, a nod to my progress and personal pride. But with the minibike and tractor already occupying space in the garage, the Monza was a practical fit.

In the fall of 1974, I purchased a new Chevrolet Monza—a sleek, compact V8 that suited my daily commute perfectly. Arlene, however, was furious. She dismissed it as “a sports car” and refused to ride in it. Symbolically, perhaps, it was a modest indulgence, a nod to my progress and personal pride. But with the minibike and tractor already occupying space in the garage, the Monza was a practical fit.

The Centerville wives had their own rhythms. Many, married to traveling executives, called themselves “management widows.” Each morning, they gathered for coffee, Valium, and gossip. It was a ritual of discontent, cloaked in routine. And perhaps, in those whispered conversations and shared grievances, the seeds of deeper trouble were sown.

Arlene had a genuine talent for cooking and baking, and she took pride in her skills. Her kitchen was modern and well-equipped, with a fully stocked pantry, high-end appliances, and the freedom of her own car. Like many of the Centerville wives, she had access to the comforts and indulgences of suburban life—tennis matches, luncheons, shopping trips, and regular pampering at salons and spas.

Yet instead of embracing those privileges, she immersed herself in housework and grievances. And, as I would later learn, not all of it was honest. Bob recently confided that it wasn’t their mother who kept the house clean—it was he and Joe, vacuuming and dusting after school while she somehow shifted their seritude onto me. This, despite the fact that my salary could have easily supported a housekeeper.

Her resentment toward my career was nothing new. She had disliked my time in the Air Force, despised my role at AEL, and bristled at my position with S&S Associates. Now, she resented my work at JCPenney. The marriage counselors we saw echoed her frustrations, suggesting that I was trying to “buy my family’s love with material things” and advising me to leave my job for one that allowed more time at home.

But with all due respect to her father, I could not be that husband. He was a man of routine—leaving for work at 6 a.m. with his lunch pail, clocking out at the four o'clock whistle, and settling in for the five o'clock news and a nap, followed by supper at six. That life worked for him, and I respected it. But it wasn’t mine.

I enjoyed my work. I thrived in leadership and responsibility. I took pride in my facility and the team I hired and managed. I appreciated the prestige that came with success. I liked dressing well, living in a beautiful home, enjoying evening cocktails, and dining out at eight. These weren’t distractions—they were the rewards of dedication, and they reflected the life I had built through effort and ambition.

But Arlene had a different vision for our lives—and when I refused to change, she took drastic steps to undermine mine. I played tennis once a week with three colleagues, a simple outlet for camaraderie and stress relief. One afternoon, Caroline from my parts department filled in for one of the guys who couldn’t make it. When I mentioned it to Arlene, she became livid.

Without hesitation, she contacted my boss and accused me of being involved with a female employee. The accusation was baseless, but it triggered a formal response. John Weatherford, manager of the Columbus Service & Parts Distribution Center, came to our home on behalf of my manager. He didn’t press the issue directly, but his message was clear: a happy wife was essential for JCPenney to retain their managers. It was humiliating—not just because of the accusation, but because of what it revealed about the fragility of my home life.

The sting was sharper because I had broken ground professionally. Caroline was the first woman to ever be hired into a parts department—a role traditionally held by men due to the physical demands of carry-in repairs like televisions and lawn mowers. However, Mike was my parts manager, and I had hired Caroline as his assistant because I believed women brought a level of precision and attentiveness that was vital to inventory control.

Moreover, I had also hired Carla for our front office. Her striking beauty was undeniable, and I passed on her application, worried it might stir gossip or criticism among my colleagues. But her determination, warmth, and poise eventually dispelled those concerns.

Still, her presence didn’t go unnoticed. Men from the business across the street once hung a banner on their lawn that read, “We Love You Carla!” It was lighthearted, yes, but it spoke to the impression she made wherever she went. Still, it was her professionalism that truly set her apart.

Carla became the best call taker in the region. She had a gift for diffusing tension, even with the most irate customers. Whether someone had purchased a lemon or simply needed to vent, she could turn frustration into laughter. Her empathy and quick wit transformed complaints into conversations—and often, into loyalty. She wasn’t just a pretty face; she was the voice of our service center, and she made that voice unforgettable.

My two female Assured Performance Plan sales representatives were equally exceptional. Despite having only one full-line store, our APP sales were second only to the Pittsburgh service center, which served three full-line stores. Their success was a testament to their talent, not gender.

Shortly after the incident with Arlene, JCPenney offered me a new opportunity: to manage the company’s first computerized Product Service Center in Camden, New Jersey. It was a major step forward, and I saw it as a chance to reset.

Arlene rarely left the house—not even to check the mailbox at the end of the driveway. I hoped the move might rejuvenate our lives and offer the boys a fresh adventure. I wanted to believe that change could still bring healing.

Divorce New Jersey Style

“Nice people don’t necessarily fall in love with nice people” Jonathan Franzen

In Dayton, OH, I ran one of the most well-regarded service centers in the country. My methods for dispatching and record-keeping became a leading example in product service.

In Dayton, OH, I ran one of the most well-regarded service centers in the country. My methods for dispatching and record-keeping became a leading example in product service.

In 1978, JCPenney asked me to manage their first computerized Product Service Center. They picked the Camden, NJ center because of its size and closeness to the New York City headquarters.

This promotion put us in the top 14% of American households. I took pride in being a successful father, husband, provider, and business manager.

I arrived in New Jersey ahead of my family, eager to settle into my new role and begin the search for a home. When Arlene joined me, she quickly made her feelings known: the houses in nearby towns—Collingswood, Audubon, Cherry Hill, Marlton—simply didn’t impress her. None felt quite right. Then we discovered Medford.

Nestled in Sherwood Forest at the edge of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, the house at #4 Robin Hood Drive had an unmistakable sense of adventure. It was a model home the developer had decided to sell, and it captured Arlene’s heart instantly. Across the street, one of Medford’s scenic lakes shimmered in the afternoon light. Though the commute to work promised to be long and often congested, the decision was clear: this was our home.

The 2,600 square-foot center-hall colonial offered timeless charm. Hardwood floors stretched throughout, with pegged hardwood in the dining room adding a touch of craftsmanship. Chair rails adorned every room, lending elegance and cohesion. The family room featured a brick wall with a fireplace, mantle, and log bin—perfect for cozy evenings. Sliding glass doors opened to a 12-by-16-foot screened deck, overlooking the dense, whispering woods of the Pine Barrens.

To preserve the model home’s polished aesthetic, we enlisted professional decorators. The focal dining room wall was papered above the chair rail with a hand-painted cherry blossom print, delicate and serene. The living room boasted rich grass-cloth wallpaper below the chair rail, adding texture and warmth. Every piece of artwork was selected with care, chosen to complement the spirit of each room.

With the promotion came prestige and a generous salary, but also more responsibilities. My days grew longer, often stretched thin by a one-hour commute and the task of implementing a new computerized system. The excitement of initiating a new national project was tempered by discontent at home. Within a month, Arlene’s demeanor shifted—resentment began to surface, quiet at first, then unmistakable.

We had just completed the final touches on our beautifully decorated home when, one morning as I dressed for work, she delivered a blow I hadn’t anticipated. Calmly, almost clinically, she informed me that she had spoken to a lawyer, cashed my monthly paycheck, and emptied our bank accounts. In the days that followed, I learned she had also spoken to neighbors, painting me as controlling and abusive—a narrative I hadn’t seen coming.

As was my habit, I had kept only $20 from my paycheck for lunch and incidental expenses. Now, with no access to funds and the walls of my life shifting around me, I found myself in unfamiliar territory. I consulted a lawyer, who advised me to cancel all credit cards and move into the guest bedroom. But I wasn’t ready—not emotionally, not spiritually—to accept the full weight of what was happening. The ground beneath me had shifted, and I was still trying to find my footing.

In an effort to maintain peace at home, I moved into the guest bedroom. But Arlene was already several steps ahead, following her lawyer’s advice with calculated precision. I quickly found myself restricted in ways both petty and cruel. I wasn’t permitted to eat anything she perpared and I was denied access to the washer and dryer. As shocking as these indignities were, they were just the tip of the iceberg.

One evening, I reached for a cookie she had baked, left cooling on the kitchen table. Without warning, she leapt onto my back, clawing at my face in an attempt to retrieve it. I broke free and fled upstairs to the master bedroom. Moments later, she burst in, threw herself to the floor beside the nightstand, grabbed the phone, and called the police.

When the officers arrived, she claimed the scratches on my face were the result of her defending herself against my alleged abuse. Despite my injuries and the absurdity of the situation, they instructed me to leave the house. I drove to a nearby “drive-up motel,” seeking anonymity and a place to recover. In the solitude of that room, I cleaned my wounds, iced the swelling, and used the small first aid kit I kept in my car to apply Band-Aids to the bloody scratches.

Not long after, she orchestrated another cruel maneuver. One evening, after a successful day hosting senior executives—including the national service manager from New York, the regional service manager from Pittsburgh, and John Weatherford from the Columbus Distribution Center—we went out to dinner to discuss the future of computers in product service. They were impressed, and I felt proud of the work I had done.

But when I returned home, the mood shifted dramatically. The guest bedroom lights wouldn’t turn on, and as I stepped forward, I felt something soft beneath my feet. From the dim glow of the hallway, I saw that Arlene had removed the bulbs from the lamps and thrown all my clothes out of the closet, scattering them across the floor.

Furious and bewildered, I stormed into the master bedroom and grabbed a lamp from the nightstand, intending to restore light to my room. As I crossed the hall, she seized the trailing cord, wrapped it around the stair railing knob, yanking the lamp from my hands and breaking the knob in the process.

Then, in a sudden burst of rage, she struck me on the head with the lamp. I fled back into the master bedroom and locked the door behind me, trying to protect myself. Moments later, she kicked the door open, splintering the frame. Once again, she threw herself to the floor beside the nightstand, grabbed the phone, and called the police.

By the time the officers arrived, the children were awake, standing in the hallway. She silenced them and sent them back to bed before spinning her story. When the police asked about the door, she claimed I had kicked the door down after coming home drunk one night—a performance delivered with conviction. But I was never drunk. I showed the officers the mess in the bedroom, the broken knob, the scattered clothes. I believe they saw through her act, though no one said so aloud.

In thirteen years of marriage, I had never once been drunk or violent. Yet once again, the police instructed me to leave my own home. This time, they allowed me to take a few belongings. I spent the night at my office, grateful that the JCPenney managers—who had flown in for our meeting—were heading to the airport early the next morning. They never noticed I was still wearing the same suit.

My lawyer advised me to retrieve whatever I could from the house. This time, I listened. I took a few cherished lithographs and hid them in my office, quietly safeguarding what little I had left. But living off my American Express and gas cards quickly drained my credit. I was supposed to see the boys that weekend, but I had no money—not even enough for a proper meal.

I began living at the office. I shaved in the men’s room and slept on the sofa in the ladies’ restroom, and I hoped no one would discover my situation. I tucked my belongings into my office credenza and arranged for my paychecks to be sent directly to work, keeping my personal situation hidden from colleagues.

The next time I returned to the house, I found all my clothes stuffed into trash bags and tossed onto the front lawn. The locks had been changed. Arlene had instructed the boys not to answer the door. I was living the nightmare she had orchestrated.

It took nearly my entire next paycheck to cover bills and secure a modest one-bedroom apartment. I rented a truck and salvaged what I could—a bed frame, some electronics, and a few personal items from the house. After purchasing the bare essentials—a mattress, dishes, utensils, and a coffee maker—I began learning the art of frugality. It was a humbling chapter, but one that marked the beginning of a quiet resilience.

Just as I began to regain my footing, Arlene struck again. She told me the boys would be away at Boy Scout camp for the weekend, so our usual visit would have to wait. I believed her—after all, the boys were active in Scouts, and I had no reason to doubt their outing.

But the following weekend, when I arrived to pick them up, the house was vacant. Every door and window was locked. I had to hire a locksmith just to get inside. What I found was staggering: the house was stripped bare. Furniture, window treatments, linens, artwork—gone. The deck and garage were empty. She had vanished without a trace.

Eventually, I discovered a few of my books up in the attic, but my military and college records were missing. I stood in the hollow shell of what had once been our home, unsure how to begin again. I still had an apartment lease and mortgage payments to manage, and the weight of uncertainty pressed heavily on my shoulders. Looking back, I wish I had reclaimed the house then and there. But I had no idea the divorce would stretch on for three long years.

Judge Ferrelli allowed Arlene’s lawyer to reschedule the hearings thirteen times. I spent countless hours alone in the Mt. Holly courthouse, waiting in sterile hallways and silent chambers. It was unsettling to see my attorney and hers sharing lunch together in the courthouse café—professional courtesy, perhaps, but it felt like betrayal.

Yet even that paled in comparison to what came next.

The old Mt. Holly courthouse loomed with its high ceilings and echoing halls, a place where justice was meant to be served but often felt like theater. As I waited alone, I noticed a woman seated nearby, quietly crying beside her attorney. Their conversation, though hushed, carried through the marble corridor.

The lawyer leaned in, her voice firm and rehearsed: “You need to provoke a fight. Call the police. Claim abuse.” The woman hesitated, visibly shaken. “I don’t want to lie,” she whispered. But the lawyer pressed on. “The police will make him leave the house. That’s your chance to change the locks. You have to do this to get the judge on your side.”

It was déjà vu—an eerie mirror of my own experience. I had lived through the same tactics, the same manipulation of truth. Watching it unfold again, so casually, confirmed what I had come to believe: that some divorce lawyers do not seek resolution—they cultivate conflict. Their approach is mercenary, and the courts that enable them, with their endless delays and quiet complicity, become less a sanctuary for justice and more a stage for duplicity.

What should have been a process of healing and closure instead became a performance—one where truth was bent, time was weaponized, and dignity was bartered for advantage. And now, I was watching it play out again, like a script written not for fairness, but for strategy.

©Copyright 2001 Charles Tyrrell - All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice