Technical Careers

An Autobiography

Cincinnati Public Library

“The stories of the people I hired during my years as Shelving Department Supervisor are unforgettable”

In August 1958, just a month shy of my 18th birthday, I began working as a “Page” at the main branch of the Cincinnati Public Library. The pay was 90 cents an hour, but the library was a cathedral of curiosity—a perfect haven for a young mind hungry for knowledge.

In August 1958, just a month shy of my 18th birthday, I began working as a “Page” at the main branch of the Cincinnati Public Library. The pay was 90 cents an hour, but the library was a cathedral of curiosity—a perfect haven for a young mind hungry for knowledge.

Each book carried a label that mapped its place in the world of subjects. This is the Dewey Decimal System, a numerical architecture that organizes books with elegant precision. Shakespeare, for instance, has his own number: 822.33. The longer the number, the more specific the subject. Sports live under 790, ball games under 796.3, and golf under 796.352.

Books are further sorted by author, but Cincinnati’s library used the Cutter Classification, which allowed for alphanumeric sorting—even when no author was listed or the title lacked a defining word.

What truly set the library apart was its division of the ten Dewey classifications into physical departments. Patrons could browse entire subjects without consulting the massive catalog files. It was intuitive, tactile, and brilliant. In the Air Force, I adopted this system for the Biloxi Air Force Base library, helping foreign military personnel navigate the library with ease.

The first floor departments held Philosophy & Religion and, History & Literature subjects. There was also a cozy “Browsing Room.” It was a library within the library filled with popular titles on all subjects. The second floor housed Business & Industry, Language & Science, and a vast Reference Book section. The third floor was a cultural trove—Art & Music, a Rare Books Room, a movie theater, and the library's catalog department.

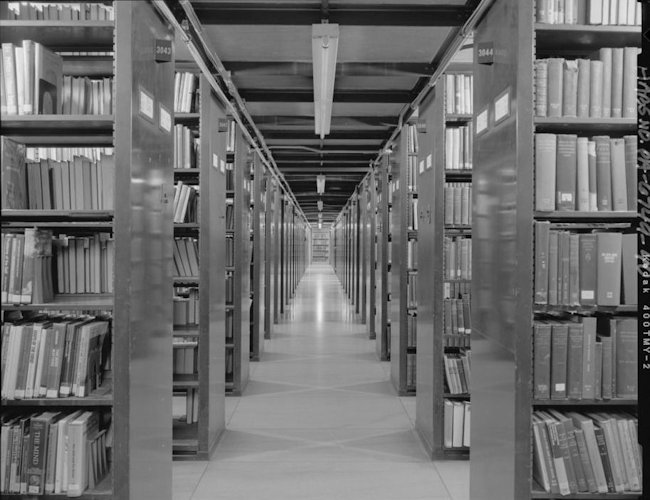

Beyond the public floors were four “stack levels,” packed with millions of overflow books, including oversized volumes—quarto, folio, and elephant folio. Two stack levels below the first floor served its departments; two between the second and third floors served theirs.

Stack levels were not open to the public. Pages worked from these stacks. When a patron requested an item shelved in a stack level, the Page would retrieve the item and send it via dumbwaiter to the main floor. When books were returned, Pages were tasked with sorting and reshelving them in their original locations on the main floors or in the stack levels.

Stack levels were not open to the public. Pages worked from these stacks. When a patron requested an item shelved in a stack level, the Page would retrieve the item and send it via dumbwaiter to the main floor. When books were returned, Pages were tasked with sorting and reshelving them in their original locations on the main floors or in the stack levels.

Lunch breaks were spent in the boiler room, where pinochle reigned. I learned quickly and became one of the top players. We played “a penny a point and a nickel a set”—except on paydays, when the stakes doubled. I often walked away a winner.

On paydays, I’d treat myself to a new 45 RPM record. I took pride in my appearance—always wore a tie with a crisp white shirt laundered at Sam Yee’s Laundry at 10¢ a shirt. Sam and his wife always gifted me with a box of Chinese tea at Christmas.

Eventually I earned a promotion to Shelving Department Supervisor. That raise helped me buy my 1957 Chevy.

The library was more than a workplace—it was a stage for stories. I interviewed a young man from Kentucky who asked me to fill out his application because he struggled with reading and writing. Under “Hobbies and Interests,” he earnestly said “cars and women.” He wasn’t hired, but not because of that answer.

Then there was Charlie Bull, who worked part-time and had as much hair growing from his ears and nose as on his head. And the Burmese tax collector who traveled village to village by canoe, lived in a tent, fished and hunted for food, but fled his country when the Japanese invaded during WWII. But the most unforgettable figure was Fredrich Kotva.

Fred had been a fighter pilot in the Luftwaffe during WWII. After the war, he defected to Hungary, and during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, he fled to the U.S. He lived at the Friars Club, a Catholic refuge for immigrants, when he was hired at the library.

Fred spoke seven languages fluently. He bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder to refine his accents and a 35mm movie theater projector—not for home movies, but for something greater that we did not understand. He explained that, before the war, he had been a film producer and director in Germany.

With an engineering degree from Germany, Fred was hired by WLW radio to launch their cutting-edge broadcast equipment. He earned enough to open a machine shop, where he invented a film splicing device and secured a U.S. patent.

Soon, Fred was assigned to the Films & Recordings Department. There, a machine was set up to repair damaged films, and Fred transformed that machine. One day, I saw the F & R machine operating autonomously—rewinding, splicing, reeling. Fred had re-engineered it.

When Fred announced his departure, the library held a send-off unlike any I’d seen. He had earned four U.S. patents and donated two to the library: one for the F & R machine, and another for a device that automatically switched 35mm projectors between reels without a projectionist.

His fourth patent was acquired by Bell & Howell. Fred became a millionaire and moved into a penthouse in one of Cincinnati’s most prestigious buildings. I never learned the details of that patent, but thinking back about Fred's discussions on 8mm film, I suspect it may have influenced the development of Super 8 film.

Fred often blew a kiss and said, “I love America. Truly the land of opportunity.” And he meant it.

Air Force ECM Technician

“In the U.S. Air Force I specialized in Electronic Countermeasures”

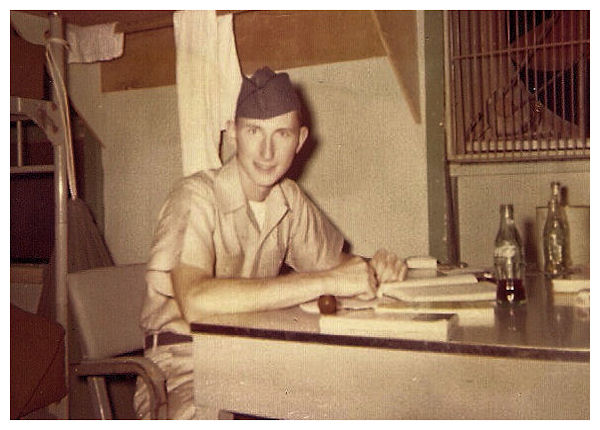

It was my twenty-first birthday, and I was sipping a milkshake at Frosty Freddy’s, set inside Lackland Air Force Base in Texas. Not the typical celebration for a young man entering adulthood—but I was a new recruit in the U.S. Air Force, and life was already shifting in unexpected ways.

It was my twenty-first birthday, and I was sipping a milkshake at Frosty Freddy’s, set inside Lackland Air Force Base in Texas. Not the typical celebration for a young man entering adulthood—but I was a new recruit in the U.S. Air Force, and life was already shifting in unexpected ways.

I had left my job at the Cincinnati Library for better pay at Alber’s Super Market—only to be laid off. Unemployed and facing the looming draft, with aspirations of becoming an electronic engineer, I joined the Air Force under the Enlist and Train With Your Buddy Program. I enlisted with two friends, but never saw them again after arriving at Lackland.

Boot Camp was grueling: marching, an abrasive drill instructor, the ear-splitting gunfire on the rifle range, obstacle courses, and endless drills. Yet on that birthday, we were granted a squadron pass—a small freedom that felt like a feast after two weeks of rigid training.

After six weeks, I was sent to Biloxi, Mississippi, for training in Electronic Countermeasures (ECM). I was eager to begin my formal education in electronics, but while waiting for classes to begin, I volunteered to assist at the Base Library—thanks to my experience at the Cincinnati Public Library. The library was great duty, quiet, clean and air-conditioned.

As is typical in libraries, all the books were organized by Dewey Decimal number. I noticed foreign students struggling with the Dewey Decimal system and proposed reorganizing the library by departments like the Cincinnati library. The librarian agreed and entrusted me with the task while she and her husband vacationed.

When she returned, she was so impressed she invited base officials to see the "new library." Among them, her husband, a colonel, who suggested I abandon electronics for another military career under his guidance. However I didn't take his advice and persue his proposal—but I’ve often wondered what might have been.

When classes began, I dove into electronics—most of it familiar from my Ham Radio training. Here I learned powerful transmitters that generated radar-jamming "white noise" in the S and X bands designed to protect aircraft from detection by radar and guided missiles. The X-band signal (8–12 GHz) traveled to the antenna via waveguide, not cable.

I studied hard earning a 98 out of 100, hoping to stay in Biloxi as an instructor. But I was sent to Plattsburgh AFB in northern New York—home to the 380th Bomb Wing.

Plattsburgh was a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base. The base housed B-47 bombers and a squadron of KC-97 refueling tankers. The B-47, with its swept wings and jet-assisted (JATO) takeoff, was a marvel of its time. Capable of flying at 600 MPH, the B-47 was the fastest plane built, and therefore had only tail guns.

Plattsburgh was a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base. The base housed B-47 bombers and a squadron of KC-97 refueling tankers. The B-47, with its swept wings and jet-assisted (JATO) takeoff, was a marvel of its time. Capable of flying at 600 MPH, the B-47 was the fastest plane built, and therefore had only tail guns.

I maintained ECM transmitters and chaff dispensers. Chaff consists of packages of tiny metal strips and reels of metal "tape." The packages can be released in large quantities, creating a "metallic cloud" to confuse enemy radar and missiles. The metal tape could also fall across power lines, causing short circuits and power outages.

Winters were brutal in Plattsburgh. I learned all about snow measured in feet rather than inches and wind-chill factors that could drop temperatures to 70° below zero. We brought car batteries inside at night and used ropes installed along sidewalks to fight the wind and blinding snow.

Even though I received commendations for inventing a device that halved our flight line workload, I never made Sergeant. A Take-off Priority (TOP) incident involving an X-band transmitter that failed before takeoff, nearly led to a demotion. While installing the new transmitter, the B-47 taxied to the runway. Hearing the engines rev, I hurriedly finished and dropped down from the plane forgetting to activate the transmitter.

The plane scored poorly on countermeasures warranting a possible demotion but my commander defended me, citing a similar oversight by a co-pilot who forgot to turn his "jammers" on during his training mission. I stayed an Airman 1st Class, but the lesson stayed with me.

On October 16, 1962, the world changed. A U-2 flight confirmed that Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev had placed medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba. Our alert planes—already loaded with nuclear weapons and ready for war—were deployed. We scrambled to prepare every flyable B-47 with nuclear weapons, install tail guns, ammunition, and wartime countermeasures.

For weeks, we lived on the brink of potential nuclear war, watching WWII films narrated by Walter Cronkite during our 12-hour shifts. When Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the missiles, the crisis passed—but the memory never did. The Red Phone was born, and the nuclear arms race began steps toward a nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

During the alert, I missed dancing at Brodie’s Bar, the girl I’d just started dating, and her family’s Thanksgiving dinner. By the next November, though, she was my wife. A year later, I was a father.

American Electornic Labs

“'We installed ECM systems into tanks, Jeeps, and airplanes”

While I was stationed in Plattsburgh, I got married and welcomed my first son. As my enlistment was coming to a close, my wife insisted that we transition to civilian life and expressed her desire not to live in Ohio. Therefore, to prepare for civilian life, I sent out resumes to electronic companies in New York and Pennsylvania.

While I was stationed in Plattsburgh, I got married and welcomed my first son. As my enlistment was coming to a close, my wife insisted that we transition to civilian life and expressed her desire not to live in Ohio. Therefore, to prepare for civilian life, I sent out resumes to electronic companies in New York and Pennsylvania.

During my time at Plattsburgh AFB, I became skilled at ECM (Electronic Counter Measures) systems on B-47 aircraft, repairing ALT-7 transmitters, and I received training on rebuilding the transmitter magnatrons.

American Electronics Labs (AEL) in Lansdale, PA. had responded to my resume and was the last company on my list of interviews. The company focuses on designing and manufacturing ECM transmitters and radar-warning receiver systems, and offering electronic antenna engineering services for military communications. In addition, they develop advanced integrated circuit components. My interview there seemed like a fantastic opportunity.

AEL had a contract with the Army to install ALT-7 S-band transmitters into M-113 Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs) for use in Vietnam. At AEL, no one was knowledgeable about operating the transmitters and I was well-versed in ALT-7s, capable of even rebuilding their magnetrons. I received and accepted what I believed was an excellent offer from the company.

I was brought on board AEL in the Systems Department, where a system of three transmitters was installed in each M-113 tank. Each system was interconnected through a complex network of cables. My responsibility was to test, troubleshoot, and ensure that the entire system was operational for Army acceptance.

Initially, the project was limited to tanks. However, the Army soon recognized that jamming radar signals was not as critical as the need to disrupt every-day communications against guerrilla and Liberation Army units in Vietnam.

Meanwhile, AEL developed an advanced communication ECM system consisting of receivers, transmitters, spectrum analyzers, and a random Morse Code generator (which I contributed to designing). This compact system was housed in a "pod" that could be mounted on the back of a Jeep for mobility. A telescoping antenna could be quickly raised into position from the front bumper. The Army was impressed, leading to a new contract.

It was a highly impressive setup with the sleek pod securely mounted on the Jeep and the attached trailer housing a jet engine generator that powered the entire system. The Army took great pride in their new ECM electronics, and when several NATO nations organized a conference in Anzio, Italy, to showcase their best electronic warfare equipment, the US Army chose to demonstrate its new AEL system.

As a leading systems technician, I was selected to support the demonstration in Anzio, Italy. Given the complexity of the system, I needed to bring sufficient test equipment to handle any potential failures. I flew directly to Rome while the Jeep with its electronics, trailer, and generator was shipped to Florence, Italy. However, it took weeks for the equipment to arrive in Florence and be transported to Anzio.

On the day of the demonstration, everything worked perfectly, impressing the audience. However, the U.S. Army Lieutenant overseeing our demonstration was disappointed. He thought it would be entertaining to grill a hot dog or roast a marshmallow in the jet blast of our generator, but his plan fell through when I couldn't find hot dogs and found it impossible to describe a marshmallow to any local merchant.

The following year, AEL secured another Army ECM contract; to equip two airplanes with the "Jeep systems." Each airplane would have five systems installed. The installations took place in San Diego, California, while testing and training were conducted in Mesa, Arizona. Following this, the planes were destined to disrupt Vietcong CW communications in Vietnam.

I made multiple trips to San Diego to evaluate the installations and several more to Phoenix for testing and training. Numerous issues emerged during the training operations. Aside from the operators experiencing motion sickness, the transmitters were shutting down when the airplanes banked to the left.

My evaluation revealed that the transmitters were shutting down because they were overheating. However, the Boeing engineers argued that the overheat sensors were faulty and shutting the transmitters down due to the manuevers of the plane.

After digging deeper, the engineers discovered the truth: the fan-driven exhaust system worked fine—until the plane banked left. That maneuver created a vacuum outside the exhaust, trapping heat inside the exhaust. The transmitters were overheating. The sensors were doing their job. Without them, the transmitters might’ve been cooked beyond repair.

Boeing redesigned the exhaust system. We got all systems operational. The deadline was met. The Army approved.

The Army had hoped to send me to Vietnam for a year to continue support and training, offering to triple my salary, tax-free. Although I would have held a civilian rank equivalent to a Colonel, my wife warned me that if I accepted this position, she and the boys would not be there when I returned home.

As a devoted father, I prioritized my family and turned down their offer. Meanwhile, I had spent the last six years studying physics and electronic engineering at LaSalle College. Unfortunately, President Richard Nixon had imposed a national wage freeze and suspended all government contracts, dimming my hopes, sacrifices, and hard work for a career in electronic engineering.

Seifert X-Ray

“Radio frequencies are under 300 MHz. Radar is under 1,000 MHz. X-rays are in the 30 Trillion MHz range“

This short-lived career began in the shadow of loss. After the death of my mentor and boss, Sy Hochman, I was unemployed. I had served as CEO of Service in Electronics under S & S Associates, and his passing marked the end of that chapter.

This short-lived career began in the shadow of loss. After the death of my mentor and boss, Sy Hochman, I was unemployed. I had served as CEO of Service in Electronics under S & S Associates, and his passing marked the end of that chapter.

Next door to S & S was Seifert X-Ray, a small firm specializing in industrial x-ray equipment for the Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) sector. With only two employees, Seifert often relied on our office for essentials like copying and faxing. Over time, we built a strong rapport.

Deiter Market, Seifert’s CEO, couldn’t match my previous salary, but he saw potential. He offered me a role as service manager, hoping to expand repairs beyond Seifert’s own products. I knew nothing about x-ray technology, but I accepted. The job covered my expenses, and I was eager to stay productive.

The transition was stark. I traded suits and office meetings for overalls and warehouse work. Industrial x-ray tubes were housed in tanks of dielectric oil and powered by high-voltage generators that hurled electrons from cathode to anode, producing x-rays. It was messy. It was dangerous.

Unlike medical x-rays, which penetrate soft tissue, industrial units were designed to pierce six inches of steel. The primary beam could cause severe radiation burns, and scatter radiation posed long-term health risks. We tested units by lowering them into an underground pit, hoping the earth would absorb the beam. Lead shields were available—but rarely used.

One day, while Deiter was away, a cautious associate of his from the medical field visited. When I was about to test a repaired machine, I lowered it into the pit and rolled out the lead shields. He brought a Geiger counter. When I activated the unit, the counter went wild. I saw his panic and shut it down immediately.

Upon Deiter’s return, we investigated. The pit had flooded—the water table had risen. Instead of absorbing the x-rays, the water reflected them, bouncing radiation off the steel rafters. I don’t know how long that had been happening, but I never experienced side effects.

Despite the hazards, I became skilled at the work. I appreciated the simplicity of metric tools—no fractions, no conversions. Just logic. I’ve never understood why the U.S. resisted the metric system.

During my time at Seifert, the Alaska Pipeline was under construction, creating a surge in demand for NDT engineers. Every weld needed x-raying. The pay was excellent, and Deiter urged me to join him in Alaska. But the idea fizzled—likely vetoed by our wives.

In hindsight, it was for the best. Within a year, I received a call from JCPenney. They had found my résumé from when SIE closed and wanted to interview me for the role of Product Service Manager.

It was a perfect fit. The regional manager was impressed by my grasp of service operations—thanks to procedures I had initiated at Service in Electronics. The only new wrinkle was in-home service, but in time, I actually revolutionized their dispatching methods.

©Copyright 2001 Charles Tyrrell - All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice