Programmer

An Autobiography

Apprentice Programmer

“I developed a hotel/motel program that could achieve a 90% fill rate.”

Management had been rewarding, but I felt the pull of something new. After years of leading teams and building systems, I was ready to pivot—toward programming, a skill I had taught myself while working with JCPenney’s Motorola computer.

Management had been rewarding, but I felt the pull of something new. After years of leading teams and building systems, I was ready to pivot—toward programming, a skill I had taught myself while working with JCPenney’s Motorola computer.

Though I had limited formal training, I had a knack for creating useful software. Still, when I scanned job listings, I saw unfamiliar languages—Cobol, Fortran, C++, RPG. The only term I recognized was “Four-Phase,” a reference to the obscure system I had worked on, which no one seemed to understand.

Only recently did I learn that Four-Phase Systems, Inc., founded by Lee Boysel, was a pioneer in semiconductor memory and MOS LSI logic. Motorola acquired the company in 1982, but back then, it was just a mystery to most.

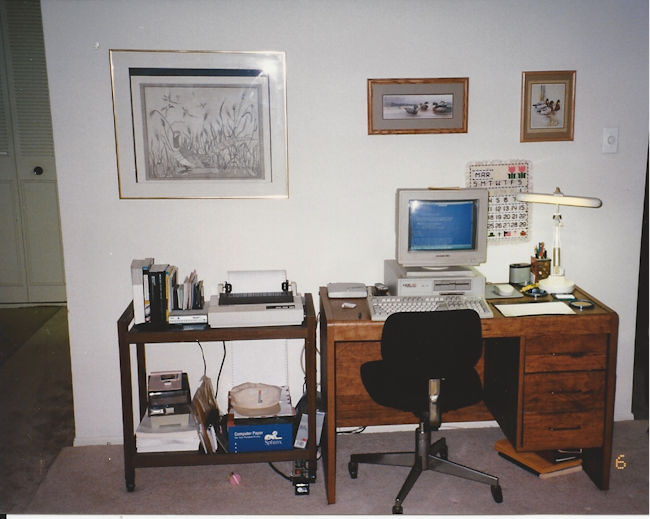

What truly intrigued me were the emerging Personal Computers. As friends and neighbors began buying PCs, I helped them learn the basics. But I missed programming. So I bought a Commodore 64, a hard drive, and a dot matrix printer. I connected it to a small television and dove into DOS—a language that felt familiar, like the one I’d used on the Motorola mainframe, but without the need to compile.

I wanted to build something useful. Payroll software seemed promising. I designed a program that managed employee records, editable tax files, and printed paychecks with detailed stubs. Teaching the computer to write checks was a challenge—it had to convert numbers into words. A check for $262.83 needed to print: Pay: TWO HUNDRED SIXTY TWO and 83/100. I cracked it, saved the routine, and launched the program in August 1987. But marketing it proved difficult.

Next, I turned to real estate. With experience in both sales and mortgages, I built a program that compared PITI and settlement costs across three loans. My friends loved it. Fox & Lazo Mortgage bought it. Crestmont Federal, where I worked, didn’t.

Then came the motel challenge. A colleague asked if I could build a room assignment program for his relative’s Jersey shore motels. After studying the business, I created software that could push occupancy to 90%. It tracked every room and adjusted reservations for maximum efficiency. I completed the 9,990-line program on November 22, 1988. But when they realized they’d need to buy computers, interest vanished.

Undeterred, I hit the road—Atlantic City to Cape May—lugging my Commodore to demo the software and promising it would pay for itself in months. For motels with computers, I created a disk that allowed a 30-day free trial. Still, no takers—until Hampton Inn showed interest. But they wanted kitchen and restaurant features. I knew it would take months to learn the food service industry and integrate it. The project stalled.

My next venture was for a law firm where my girlfriend worked. They had PCs but no practical software. I built a program to organize caseloads, track venues, and monitor communications. They especially loved the feature that printed lists of unresolved cases by venue—perfect for planning business trips. They didn’t pay me, but they treated us to a lovely dinner.

As PCs spread, DOS faded. Visual Basic was the new frontier, but converting my programs would be a massive undertaking. Meanwhile, Microsoft was releasing new software weekly. I could spend months on a single program, only to see the landscape shift again.

To earn a living, I needed to work for someone else. After being “the boss” for fifteen years, I decided: if I had to work for someone else, it would be doing something I truly loved.

Programmer Analyst

“Find out what you like best, and get someone to pay you for doing it” -- Katharine Whitehorn

In 1988, I saw my chance. A job listing for a PICK® Programmer promised a language similar to DOS and two weeks of training. It was the doorway I’d been waiting for. I submitted a résumé that leaned heavily on my DOS experience and painted my programming work at JCPenney as a cornerstone of operations. It worked.

In 1988, I saw my chance. A job listing for a PICK® Programmer promised a language similar to DOS and two weeks of training. It was the doorway I’d been waiting for. I submitted a résumé that leaned heavily on my DOS experience and painted my programming work at JCPenney as a cornerstone of operations. It worked.

I was hired by Business Operating Systems and Software—BOSS—in Blackwood, NJ. The salary was modest, but the work was meaningful. I was finally doing what I loved, and earning a steady income.

BOSS sold proprietary software for payroll, payables, receivables, and general ledger. They had two programmers when I joined, and brought on Sandy at the same time—a single mother and Cum Laude graduate in Computer Science. We were paired for our first assignment: supporting a new PICK installation at a dental tools manufacturer in Northeast Philadelphia. The commute was long, but the collaboration was rich. Over time, Sandy and I became close friends.

My first solo client was a commercial landscaper with a unique inventory challenge. He bought grass seed by the pound, but his employees used it by the scoop. Fertilizers and weed killers were purchased in barrels and diluted for use. I built a system that converted scoops to pounds and concentrates to commodities. He was thrilled.

Next came a retailer for General Cable. He bought reels of cable in 1,000-foot lengths and sold them by the foot. IBM had tried—and failed—for over a year to manage his inventory. I created a program that tracked every reel within every type of electrical power cable he sold—an inventory within an inventory. It monitored usage, and flagged scrap. It was a breakthrough.

As Sandy moved on to COBOL programming at Cigna®, and another programmer left, I took on more clients—including an eyeglass manufacturer who had just acquired another company and its franchises. They needed a General Ledger within a General Ledger. Luckily, I had built a similar system for the Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill, PA. That experience helped me create a new GL program for their Dallas headquarters.

My boss and I flew to Dallas to install and test the software. Long days, hard work—but when we returned, BOSS refused to reimburse me for meals, parking, or overtime. They did, however, add my GL program to their proprietary suite.

After four years, I had outgrown the role. My pay was less than half of what the boss’s son earned, despite managing more clients and developing new software. When they hired someone to take over some of my accounts instead of offering a raise, I knew it was time to go.

I joined Larmon Photo in Abington Township, PA. Their systems ran on PICK® for retail and PRIME® for the local police department. The two were similar, and I adapted quickly. Larmon’s president, David Harrar, had spent 25 years developing PHOTOWARE®—the first system built by and for photo retailers. It was respected worldwide.

My biggest project at Larmon was a payroll program for the Washington, DC area, where employees often lived in one state and worked in another. The program handled complex tax withholdings and was scalable for global use.

But the photography industry was changing. Stores were closing, and I was the last programmer hired. My supervisor gently suggested I look elsewhere.

That led me to Lightship Corporation, a company that bought delinquent receivables and pursued full collection. I had a bright office on the 16th floor of a Chestnut Street building in Philadelphia and was finally programming in PRIME®.

To my delight, Sandy was working just blocks away at Cigna’s Liberty Place. For the next 15 years, we shared lunch nearly every day—especially in the summer, when Rittenhouse Park became our favorite spot.

One of my proudest achievements at Lightship was a mainframe program that functioned like modern email—tracking inter-office memos by sender, recipient, content, and replies. The biggest challenge? Ensuring left-justified text without hyphenation on machines that didn’t wrap lines. I solved it.

But Lightship, like many small companies, lacked stability. After a short period, they too faced closure. I returned to the classifieds.

Then came the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

They needed a PICK Programmer. I had six years of experience and knew my worth. I applied and was hired—on September 17, 1993, my 53rd birthday. The office was on Chestnut Street at 21st, and as a city employee, I had to live within city limits.

Senior Programmer

“I worked nights writing from home so PHA could pass their first HUD evaluation. No one said thanks!”

I began my tenure at the Philadelphia Housing Authority on September 17, 1993—my 53rd birthday. It felt like a fresh start, a meaningful role as a Programmer Analyst in the Information Systems Management Department (ISM). We were a small but vital team: three programmers, two print room staff, the Director, and his secretary. Our mission was clear—build systems that empowered employees, supported residents, and satisfied HUD’s rigorous reporting requirements.

I began my tenure at the Philadelphia Housing Authority on September 17, 1993—my 53rd birthday. It felt like a fresh start, a meaningful role as a Programmer Analyst in the Information Systems Management Department (ISM). We were a small but vital team: three programmers, two print room staff, the Director, and his secretary. Our mission was clear—build systems that empowered employees, supported residents, and satisfied HUD’s rigorous reporting requirements.

PHA’s headquarters at 2012 Chestnut Street placed us in the heart of downtown Philadelphia. ISM occupied the third floor, Payroll the fourth, with Accounting and Admissions next door. The parking lot bridged the two buildings, a quiet space between departments that served nearly 80,000 residents—one in four households in the city. With 1,400 employees and a $400 million budget, PHA was the fourth-largest housing authority in the nation.

To work for the city, I had to live within it. I left Jericho Manor in Abington Township and moved to Chestnut Hill Village—a spacious apartment in a proud, historic neighborhood still within city limits. My commute shortened, my surroundings improved, and I felt ready to contribute.

But PHA had never passed its annual HUD evaluation. The director was a figurehead, and HUD maintained direct oversight. Eight years into my role, I was appointed HUD Liaison during an evaluation—and uncovered a critical flaw.

HUD allowed work orders to be marked “complete” if the issue was “abated.” A broken window, for example, could be considered abated once the cold and rain were blocked—even before the glass was replaced. Our system didn’t account for this nuance. Emergency work orders were being misreported, and no one seemed to grasp the implications.

I presented my findings in meeting after meeting, but administrators dismissed the idea. So I took matters into my own hands. Working nights from home, I rewrote the entire work order system to include abated completions. It took months, but when I compared reports from the old and new systems, the difference was undeniable.

Still, administration denied my findings. However, one Site Manager out of 65 believed in the new approach. I implemented my software for his site, and when his annual reports came in, they stunned the administration. With his help, I had the proof I needed to implement my new work order software.

That year, PHA passed its HUD evaluation for the first time—and with outstanding results.

The newspapers credited the director and his staff. In truth, it was my solitary effort. The following year, I was sent to Chicago to install the same system at their Housing Authority, which had also never passed HUD. There, I saw dozens of work orders for “repair bullet holes”—a sobering reminder of the conditions many residents faced.

Despite rescuing two major housing authorities, I received no recognition. When it came time for the “Employee of the Year” award, it went to Paul Fuentes—the man who loaded paper into the printer. The reasoning? They had asked both of us to complete a task they knew was impossible. Paul said, “I’ll try.” I said, “It won’t work.” They told me I should have said, “I’ll try.”

Throughout my years at PHA, I redesigned payroll, general ledger, and work order software. I updated W2 and 1099 forms annually to match changing layouts. I even built a system to merge crime reports from PHA’s own police department with those of the city—only to have it shelved when the combined crime rate proved too embarrassing.

In 2003, PHA began transitioning from its mainframe to Internet-based systems and PeopleSoft. I was the only programmer left working on the mainframe, while others joined the conversion team. My role shifted from development to tedious report comparisons—checking PeopleSoft’s output against our legacy system.

The work I once loved became a chore. My days were filled with emails and cubicle silence. I was still responsible for Resident Services and Work Orders, but development was gone. So was the spark.

Then came 2004. I had booked a Mediterranean cruise—paid in full, non-refundable. When my vacation time approaced, PHA denied it. They threatened to fire me if I went.

So I chose something better. I chose to retire.

Web Design

“In 1990 I discovered the Internet and taught myself HTML & JavaScript”

It all began in the late ’90s with a dial-up subscription to AOL. The Internet was still a mystery to most, but I was captivated. AOL’s cheerful “You’ve Got Mail” became the soundtrack to my evenings, and soon I was exploring websites, learning how they worked, and imagining what I could build myself.

It all began in the late ’90s with a dial-up subscription to AOL. The Internet was still a mystery to most, but I was captivated. AOL’s cheerful “You’ve Got Mail” became the soundtrack to my evenings, and soon I was exploring websites, learning how they worked, and imagining what I could build myself.

That curiosity led me to HTML—HyperText Markup Language—the backbone of the web. In 2000, I bought HTML for the World Wide Web by Elizabeth Castro, and with that book as my guide, I taught myself to code. I built my first website hoping to attract clients for Pick® programming. No business came of it, but the book still sits on my shelf, a trusted reference.

As I grew more fluent in HTML, I added CSS and JavaScript to my toolkit. While others relied on templates, I wrote code from scratch—faster and more flexibly than most could manage with drag-and-drop builders. I could shape any design, any layout, any vision.

In 2001, I had an idea: what if my autobiography looked and read like a newspaper? Each “article” would be a story in my life. I launched The Good Times on January 17, 2003. It featured news stories from my personal history, an editorial page, and even classified ads—except the ads were for cars I’d owned and house I lived in, not ones for sale.

Over time, The Good Times grew from 8 to 14 pages. In April 2018, I released Volume 6. In 2023, I redesigned my newspaper for mobile devices. It lost its newspaper charm but gained accessibility.

Since my first website, I’ve published 18 websites. Some sold. Some I gave away to friends and family. Each one was a labor of love.

One of my proudest creations was a Golf Course website I built in 2003. I believed in it so strongly that I designed a colorful trifold brochure and mailed it to dozens of courses and resorts. I even went door to door at local clubs. The site featured an interactive map—click a hole number, and a photo and description appeared. You could view the scorecard alongside the map, and in some versions, see the hole from both the tee box and the green.

It was elegant. It was functional. It was unique.

But the brochure didn’t spark interest. No one asked for a demo. The site was never sold. Still, I’m proud of it. Just as I’m proud of every line of code in the “External Links” section of the menu. Those are my programs, my designs, my legacy.

The Tyrrell Kids' Family History and my Blog, were built using Blogspot HTML Builder. But like all of my work, they’re still hand-coded, line by line, with care and intention.

©Copyright 2001 Charles Tyrrell - All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice