Single Life

An Autobiography

Lindenwold - On My Own

“A dead end is a good place to turn around”

It took twelve years of marriage, seven years of night classes, and a complete career change to build a stable life for my family. Yet, one selfish wife, two greedy lawyers, and a stubborn court took it all away.

It took twelve years of marriage, seven years of night classes, and a complete career change to build a stable life for my family. Yet, one selfish wife, two greedy lawyers, and a stubborn court took it all away.

Separation was unavoidable, and I moved to a small one-bedroom apartment in Lindenwold, New Jersey, struggling with child support and alimony that consumed much of my income. The court allowed Arlene to maintain her lifestyle, while I was left in poverty.

With no furniture, I tried to collect some belongings from the house, notifying the police to avoid conflict. Arlene wasn’t home, but when she returned, she locked the doors and went to the neighbors for help.

The police were helping me remove a mattress through a window, when neighbors began taking my belongings from the truck onto their property. The police intervened and with the mattress still stuck in the window, advised me to leave with what I had.

Left with little, I bought an affordable mattress and a drop-leaf table from JCPenney, and kitchen, bath and bedroom essentials from K-Mart.

On a lark, I bought a used pool table, instead of a living room and created a game room. It was a luxury, yes. But more than that, it was a quiet act of self-respect. In that sparse apartment, with mismatched essentials and a pool table where a sofa might’ve been, I began to rebuild.

In a world that had demanded compromise, this room was pure intention. No couch, no coffee table, no television murmuring in the background. Just the satisfying click of billiard balls, the hum of music from my stereo, and the soft glow of a globe lamp casting shadows on antique-car wallpaper.

Each detail was deliberate. The dart board, mounted with care. The makeshift bar, stocked not for guests but for quiet evenings of reflection. The vintage car wallpaper—art that reminded me of the roads I’d traveled, the freedom I’d earned. And that New Yorker print? It was more than decoration. It was a nod to grit, to attitude, to the optimistic spirit I carried with me.

But while I was building something new, something precious was slipping away.

The boys had vanished with their mother. I later learned they had moved to Massena, New York, but I had no way to reach them. It seemed they weren’t allowed to contact me. On one occasion, they managed to call me at work—just a brief moment of connection—but Arlene punished them for it. She made them pay for the long-distance call out of the little money they earned delivering newspapers in the bitter cold of Massena.

It was a cruel twist. I had built a life, a home, and a career with the hope of giving my children stability and opportunity. Now, I was left with silence and secondhand stories. The game room, for all its charm, couldn’t fill the void left by their absence.

Barbara - Dance Floors and Candlelight

“Our romance unfolded with the same grace as our choreography”

Having lost my family and everything I cherished, I knew I needed to seek out new friendships and rediscover the parts of myself that had been buried beneath grief. There was a popular nightclub in Marlton that featured live bands and dancing. I longed to dance again—not just for the movement, but for the connection.

Having lost my family and everything I cherished, I knew I needed to seek out new friendships and rediscover the parts of myself that had been buried beneath grief. There was a popular nightclub in Marlton that featured live bands and dancing. I longed to dance again—not just for the movement, but for the connection.

I gave the Marlton nightclub a try. While sipping a scotch at the bar, I noticed a woman whose dancing was effortless and magnetic. She had a Dorothy Hamill haircut that bounced with every step, and something about her presence drew me in. I asked her to dance, and we clicked instantly.

Her name was Barbara Matthews, and she lived near Lindenwold at Bromley Estates. I can’t recall the exact moment I asked her out, but she accepted, and we spent the evening dancing until our feet ached and our spirits soared.

When we returned to her home, we accidentally woke her daughter—a schoolteacher who rose early each morning. On our second date, I brought two roses: one for Barbara, and one for her daughter as an apology. They were touched by the gesture.

Barbara and I shared a deep passion for dancing. After watching Saturday Night Fever, we were inspired to take up disco. Barbara was a natural—she could spin, dip, and perform lifts with grace and precision. We developed a repertoire of dazzling moves and soon became a popular couple on the nightclub circuit.

Our relationship quickly blossomed beyond the dance floor. Barbara, originally from Vermont, was an avid skier. She introduced me to Ski Mountain in Pine Hill, where I learned to ski. Once I found my footing, we spent a weekend on the slopes, and for the first time in years, life felt normal—joyful, even. That year, we joined the South Jersey Ski Club and skied across Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, and New Jersey.

Barbara wasn’t just my partner on the dance floor—she became my partner in every sense. Our romance unfolded with the same grace as our choreography: fluid, intuitive, and full of quiet surprises. Whether we were sipping coffee after a late-night dance or sharing dinner in front of the television, there was a rhythm to our connection that felt effortless.

She was affectionate without being possessive, playful without being frivolous. We shared long conversations, and the kind of laughter that comes from truly knowing someone. Her touch was gentle, her smile disarming, and her presence grounding. I never had to perform with Barbara—she saw me, not just the dancer or the romantic, but the man behind the moves.

Normal weeknights with Barbara were simple and comforting. She prepared dinner, and we’d set up the card table in the living room to watch the Eagles, Phillies, or Flyers—or play Backgammon. We always began with a gin martini, experimenting with garnishes from pickled tomatoes to squid. Eventually, I began staying overnight and driving back to Lindenwold in the morning to get ready for work.

Friday nights were reserved for happy hour at Cenneli’s, a lively nightclub and gourmet Italian restaurant with a spacious dance floor and a seven-piece band. But our favorite spot was Momma Ventura’s. Its smaller, more intimate dance floor suited us perfectly, and before long, Barbara and I were known among the regulars as Fred and Ginger.

Though Barbara was thirteen years older than me, her petite frame and youthful energy concealed her age. She was even carded twice during our time together—once at a nightclub where we weren’t known, and again on a ski trip at the lodge bar. Her spirit was ageless, and with her, mine felt renewed.

Barbara introduced me to her friends and community, where I found warmth and belonging. Her social circle included friends from Pine Hill and Marlton, such as Sherry Hackerman, Dick and Betty Goodwin, and Dick and Jennie Shultz. Sherry, Barbara's best friend, was a charming and flirtatious figure often joining our dance outings, along with Lenora from Bromley. Together, the three women were nicknamed "Charlie’s Angels."

Barbara’s Bridge Club included the Goodwins and Schultzs, and I was soon invited to play. My background in Pinochle made learning bridge easy, and her friends were patient and welcoming. When it was my turn to host, we gathered at Barbara’s house. When the Goodwins hosted, it was sometimes at the Marlton Country Club.

Visiting the Goodwins at their Mt. Holly residence was always a special experience. Their home seemed like something out of a dream—part rustic getaway, part architectural masterpiece. Nestled deep within the woods of Mt. Holly, their converted farmhouse blurred the boundaries between shelter and nature.

The sunken living room featured a glass wall lookong into a dense woods that appeared to lean in as if seeking attention. The master bathroom, also surrounded by glass, had a tree growing directly through the roof—a subtle reminder that nature came first, and the house had made space for it.

The guest bathroom was a delightful blend of whimsy and design: two old silos repurposed into a circular retreat, with glass ceilings and illuminated trees overhead. Entering felt like stepping into a woodland cathedral, where even simple acts—like washing hands or pausing to reflect—became moments filled with awe.

Control & Lies

“Arlene’s bitterness extended far beyond our marriage”

Despite my efforts to reconnect with my sons, Arlene’s bitterness complicated matters, including false accusations and control over their lives.

Despite my efforts to reconnect with my sons, Arlene’s bitterness complicated matters, including false accusations and control over their lives.

The winter our ski club planned a trip to Whiteface Mountain in Lake Placid, New York, I reached out to Bob and Joe to see if they’d like to join me for a weekend of skiing. Massena wasn’t far from Lake Placid, and they were thrilled. It felt like a rare opportunity to reconnect—to share something joyful and active, far from the strain of courtrooms and alimony battles.

I arranged for their travel and, because the ski club’s bus wouldn’t arrive until Friday night, I arranged for them to stay at a family-run hotel. The owners assured me they would be safe and well cared for. I trusted them, and I trusted my sons. But Arlene was furious. She objected to them missing school on Friday and being alone until I arrived that evening.

When I met Bob and Joe at the hotel, I was stunned—they had brought all their belongings. Their mother had insisted they return to New Jersey with me. The ski club’s bus was full, so I had to scramble to make sure they could safely return to Massena. What should have been a weekend of skiing, dining, and bonding with my sons was overshadowed by conflict and control.

Arlene had turned a moment of connection into a logistical and emotional mess. Still, I held onto the joy of seeing my boys—of watching them laugh on the slopes, even briefly. In the midst of chaos, those moments reminded me why I kept trying.

Arlene’s bitterness extended far beyond our marriage. She was often cruel—not just to me, but to her sons and even her own brother. One evening, while I was working late at the office, I received a startling phone call from a woman who identified herself as Bob’s parole officer. I was stunned. The word parole didn’t make sense in any context I knew.

She explained that Bob had come home late after delivering newspapers and got into an argument with his mother. He left the house. Arlene, in response, called the police and reported him as a runaway. When she discovered he was staying at her brother Keith’s place, she escalated the situation—accusing Keith of kidnapping Bob and requesting his arrest.

The story was murky, and the caller’s explanation of Bob’s supposed parole status was vague at best. I couldn’t make sense of it, so I decided to drive to Massena to get answers firsthand. Barbara came with me for support, though I didn’t tell anyone she’d be joining me.

Arlene insisted I meet the boys in town. It was the dead of winter, and our meeting was brief. Bob and Joe seemed physically fine, but emotionally guarded. I casually brought up the police incident, hoping for clarity, but they offered no response. I let it go.

I also arranged to meet with Keith while I was in Massena. His account aligned with what I’d heard: Bob had argued with his mother, stayed with him, and Arlene had tried to have him arrested. I asked if he knew anything about the eight rooms of furniture that had mysteriously vanished from the house. He said he’d been told I had taken everything.

It was a surreal moment, trying to piece together a narrative that had been twisted beyond recognition. Lies had replaced facts, and the truth was buried beneath layers of resentment and manipulation. I left Massena with more questions than answers, but also with a quiet resolve: I would continue to belive my sons were strong and resiliant.

Years later, Bob confided in me that the entire parole officer story had been fabricated. He recalled that Arlene had wanted Keith arrested after he slammed a beer bottle down on a server during an argument, leaving a deep imprint in the soft pine tabletop. That sounded like Arlene and confirmed that she obviously had the missing furniture from the house.

Bob remembered that the incident had caused serious tension between Arlene and her brother, and we began to suspect that Keith’s wife may have been the one who made the mysterious call—an attempt to drag me into the chaos Arlene was stirring in Massena.

Still, nothing could have prepared me for what came next. Shortly after the divorce papers were finalized, Bob called me early one morning from the Greyhound station in Massena. He and Joe were leaving for New York City, then heading to live with me. Their grandfather had given them some money, but it wasn’t enough for food, and they had no directions for how to get to New Jersey.

I instructed them to take the evening commuter bus from New York City to Mt. Laurel, New Jersey, where I would meet them. Barbara and I found them at the bus station and treated them to dinner. Their destination was now my modest apartment—with its game room and single bedroom. It wasn’t ideal, but it was the only option. The boys took the bedroom, and I stayed at Barbara’s.

Over the three years Arlene dragged out the divorce, I had rebuilt my life from the ground up. What had once been a destitute situation had become one of comfort and quiet prosperity. I was determined—she would not destroy what I had accomplished again.

Whether Bob and Joe ever fully understood how she used them to try to ruin me, I may never know. Like her mother, Arlene was a manipulator, a liar, and a thief. She stole our wealth, our savings, our home—and their youth. She locked them away in Massena, then released them without guidance, without a plan, and without a future.

But they found their way to me. And that, in itself, was a beginning.

Pine Hill - A Single Dad

“By the time I completed paying the court order, Joe was already 30 years old”

Over three years, I rebuilt my life, determined not to let Arlene destroy it again. She had taken much from us, but my sons found their way back, and though my apartment was modest, it was a new beginning.

Over three years, I rebuilt my life, determined not to let Arlene destroy it again. She had taken much from us, but my sons found their way back, and though my apartment was modest, it was a new beginning.

Barbara, ever resourceful and supportive, worked as a real estate agent and sales manager at Bromley Estates in Pine Hill, New Jersey—where she also lived. When she learned of a two-bedroom condominium available for rent, she knew it would be a perfect fit for me and my two sons. After several months in my cramped apartment in Lindenwold, we made the move to Bromley Estates.

The condo was a welcome upgrade. It featured an eat-in kitchen, which gave me the freedom to place the pool table in the dining room—a centerpiece of our new home. I purchased twin beds for the boys, who shared one of the bedrooms, and slowly, the space began to feel like ours.

Bromley proved to be an excellent environment for the boys. The community offered an Olympic-sized swimming pool and two tennis courts, and it didn’t take long for Bob and Joe to make friends and build relationships with other teenagers in the neighborhood.

Although I wasn’t entirely thrilled about Bob’s late-night Dungeons & Dragons sessions, the pool table was a hit. Their friends often gathered at our place, filling the condo with laughter, competition, and the kind of youthful energy I hadn’t felt in years.

It wasn’t the life I had once imagined—but it was a life rebuilt, one game night and pool shot at a time.

Pine Hill, New Jersey, was once a summer haven for wealthy Philadelphians seeking respite from the city’s heat. Its modest homes, originally built as seasonal retreats, still carry echoes of that quieter era. Today, Pine Hill is best known for the prestigious Pine Valley Golf Club—consistently ranked among the top courses in the U.S. and the world. Private and exclusive, it remains out of reach for most, with a membership waitlist that feels eternal.

Pine Hill was once home to Ski Mountain, where I first learned to ski. Though more of a hill than a true mountain, it was perfect for beginners and weekend practice. That slope has since been transformed into the Trump National Golf Course of Philadelphia.

Nearby, Clementon, New Jersey was once the site of Clementon Lake Amusement Park, where Bob and Joe spent countless summer days with friends. Today, the park has evolved into a splash park—another reminder of time’s quiet march.

For me, Pine Hill held a different kind of legacy.

While it offered recreation and community, it also became the backdrop for one of the most difficult chapters of my life. Living in Bromley Estates, I lost my career, my self-respect, my two sons, and eventually, I lost Barbara.

Just before Thanksgiving in 1982, JCPenney informed me that they would stop selling hardline merchandise. All product service centers would be closing on April 1, 1983. GE would take over appliance repairs, RCA would handle electronics, and independent contractors would service lawn equipment.

To avoid destroying the holidays, I was instructed to wait until January to inform my employees. When I made the announcement, it was devastating. Over the next three months, I helped sixty employees in Camden, NJ, and Wilmington, DE write resumes and find new jobs. It was a painful task, but I did it well. By the end of March, my technical supervisors had secured positions with RCA and GE, and most of my technicians and staff found work with GE or American Appliances.

Finally, I was tasked with liquidating the assets of both service centers and received six months’ severance pay. An offer came from Montgomery Ward in South Carolina for a service management role. But Bob was a senior in high school and wanted to graduate with his friends. I promised him we wouldn’t relocate.

That promise came at a cost. My search for local employment in management was long and fruitless. I applied for a service manager position at a major fuel oil company, but the owner insisted I needed hands-on boiler repair experience. I applied at a large office machine retailer, only to be told I was overqualified. I even applied for a manager role at ITT Technical Institute, but came in second—my résumé lacked formal classroom teaching.

With no job and no income, I stopped paying child support. But court orders don’t bend to circumstance, and I was swiftly labeled a “deadbeat dad”—despite the fact that my sons were now living with me. I soon learned that to legally stop the payments, I had to have the original court order reversed.

On June 15, 1983, I went to court. I didn’t hire my lawyer, Paul Meletz, because I expected Judge Ferrelli—who knew the case well—to simply terminate the support order. But Ferrelli was on vacation in Italy, and Judge Gaddos took the bench instead.

I explained that my sons were in high school, living under my roof, and that the support order no longer made sense. Gaddos banged his gavel and launched into a speech about the responsibilities of “bringing babies into this world.” I tried to clarify—they were teenagers—not babies. He refused to listen and held me in contempt of court.

When I shared the story with a friend, he mentioned that he and his lawyer often played golf with Judge Gaddos and suggested I hire hs lawyer. I did, paying a $500 retainer (about $1,600 today). We returned to court, and what followed was a theatrical performance—lawyer versus judge, full of dramatic posturing and rehearsed tension.

In the end, Judge Gaddos ruled that I must continue paying child support because, in his words, “I looked prosperous.” When I asked my lawyer what I had received for my $500, he replied that the payments would be placed in an escrow account—and that I was leaving the courthouse with him instead of the sheriff. I was livid.

To this day, I don’t know what became of the escrow money. I’ve held onto the hope that it helped with Joe’s community college tuition. What I do know is that by the time I finished paying off the court order, Joe was already thirty years old.

Meanwhile, I struggled with the emotional toll of parenting two sons who remained loyal to their mother. I had given them stable homes, good schools, sports, and a sense of responsibility—only to have my love rejected. Arlene, on the other hand, had stripped them of their childhood and their future. She had thrown them out of her home in Massena—not once, but twice.

Barbara, ever gracious, enjoyed cooking dinner for the four of us. But the boys resisted our relationship. I understood their discomfort, but I had spent the last three years rebuilding my life—making new friends, reclaiming joy. I continued spending nights with Barbara and dancing on weekends. They weren’t too young to understand. At seventeen, I was helping my mother run a business. I knew what responsibility looked like. I also knew what resilience required.

Still unemployed, I accepted the role of service manager at American Appliances—a company I’d long avoided due to its poor reputation for customer care. But the need for steady income outweighed my reservations. I stepped into the job with a clear-eyed resolve, determined to bring order to chaos. From day one, I laid out a one-year plan to reorganize their operations.

Bob was graduating high school, and to my surprise, his mother attended the ceremony. I learned she had returned to New Jersey, though no one seemed to know exactly where she’d landed. After his graduation, I arranged a job for Bob transporting merchandise between American Appliance stores and the service department.

Barbara and I continued seeing each other, though the shifting ground beneath me began to strain our connection. Eventually, the house was sold at auction for $92,000. I received just $1,700 from the sale—and gave it all to the boys. Bob bought a vintage car. Joe chose a red motorcycle.

The following year, Joe graduated high school and celebrated with his mother—not with me. Their loyalty to their mother puzzled me and I tried not to take it personally, but the silence between us spoke volumes.

My changes at American Appliances weren’t always popular, but they worked. Too well, perhaps. The technical supervisor—a longtime friend of the owner—decided the business was now manageable without me. Less than a year after I began, I was let go. It was a bitter ending to a chapter I’d poured myself into, and the sting of being replaced lingered longer than I expected.

As I struggled to afford Bromley, Bob moved in with his 16-year-old girlfriend and her parents. Joe moved in with his mother to attend community college. I told myself they were finding their own way. Still, it felt like the doors were closing faster than I could knock.

Haddonfield & Joyce

“Embrace the opportunity to fall in love and to rediscover the magic”

My successful days in management had come to an unexpected close, and at the age of 44, I found myself standing at the edge of a new chapter.

My successful days in management had come to an unexpected close, and at the age of 44, I found myself standing at the edge of a new chapter.

With no clear path back into the world I had once navigated with confidence, I pivoted toward a fresh start. I earned my Real Estate license and accepted a position at the Haddonfield office of Fox & Lazo Realty, located on Tanner Street in the heart of downtown Haddonfield.

It was a picturesque setting—tree-lined streets, colonial architecture, and a steady hum of community life. But beneath the charm, I was starting over. The office was filled with seasoned agents, many of whom had deep roots in the area and strong networks of clients. I was the newcomer, trying to carve out space in a field where relationships were currency and reputation was everything.

Though the transition was humbling, it was also a testament to my adaptability. I had weathered storms—personal, professional, and emotional—and here I was, still standing, still striving. Real estate wasn’t just a job; it was a chance to rebuild, reconnect, and redefine success on my own terms.

While working at the Fox & Lazo office in Haddonfield, a woman walked in looking to buy a home. Her name was Joyce Grey. Recently divorced, she had grown up in Haddonfield alongside her ex-husband, and both of their parents still lived in town. With two young daughters, ages eight and ten, Joyce hoped to stay close to family who could help with childcare while she worked.

Haddonfield, with its historic charm and strong school system, was an expensive place to settle. We spent a couple of weeks exploring properties in and around town, but nothing fit her budget. Then I found a cozy two-bedroom apartment for rent above a local restaurant—right on Tanner Street, just steps from her workplace. Joyce adored it and signed the lease.

Once she was settled, Joyce began stopping by the office—sometimes with lunch, sometimes with homemade treats. Petite and attractive, her warmth toward me drew attention from my colleagues. I began returning the kindness, taking her out for lunch, and soon we were inviting her daughters along when they weren’t in school. The connection deepened naturally.

Eventually, Joyce and I began dating regularly. We enjoyed dining out, dancing, and spending time with her daughters, who quickly took a liking to me. It felt like a family forming—quietly, gently, and joyfully. One evening, after dinner at her apartment, the girls asked if I could stay the night. I hesitated, unsure of the moment, but to my surprise and delight, Joyce said it would be nice if I did.

That night marked the beginning of a beautiful relationship. Joyce began celebrating every Friday the 13th as our “anniversary”—the day she found the Tanner Street apartment and we had toasted our success at T.G.I. Friday’s happy hour.

Her parents welcomed me warmly, and we celebrated holidays together like family. After three years of dating, Joyce and I began discussing marriage, though we kept it quiet. When a charming twin house went up for sale on Ellis Street in Haddonfield, we bought it together. It was the first time since my divorce that I had even considered marriage or sharing a home again.

Joyce and her ex-husband had an unusually amicable divorce. They split everything evenly and avoided costly legal battles. He visited every other Saturday from Poughkeepsie, NY, to spend weekends with the girls. He always brought Joyce a check and joined me for coffee while she helped the girls pack. Our conversations were friendly, even easy.

Occasionally, Joyce and I would drive the girls to Poughkeepsie ourselves. It gave her a chance to reconnect with old friends and gave us a weekend getaway. Sometimes, we even went on double dates—with her ex-husband and his girlfriend. It was unconventional, but it worked. It was peaceful. And for the first time in a long time, life felt whole again.

Life with Joyce had been truly good—warm, steady, and full of small joys. But Real Estate proved financially unsustainable, so I pivoted to selling mortgages. Even then, the income was modest, and I began writing PC software to supplement it. I sold a mortgage program to Fox & Lazo Mortgage Company and wrote another for the law firm where Joyce worked. I was actively seeking a programming job, hopeful that a new chapter was just around the corner.

But before opportunity could arrive, heartbreak did.

On the Ides of March 1988, I was watching the girls while Joyce worked late. She’d been working overtime more frequently, and something about it didn’t sit right. Eventually, I learned the truth: the “overtime” was a wealthy local businessman who had been pursuing her. The affair wasn’t just a private betrayal—it had become the talk of the town. I was blindsided.

Joyce saw the pain in my eyes and tried to explain. She said she had to think about her future—and her daughters’. Her new suitor was married, but he owned a bakery and luncheonette in town and one of Haddonfield’s grand Victorian homes. He flew his own airplane. I, on the other hand, was struggling to stay afloat, driving a 1979 Chrysler LeBaron with 143,000 miles on it and dreams that hadn’t yet paid off.

I had never felt such despair. I moved out of the house. Joyce reimbursed me for my half, but the money meant little compared to what I lost. I missed her. I missed the girls—those two had become like daughters to me. Their laughter, their presence, had filled the house with life.

To cope, I began writing a daily journal. Pouring my thoughts onto the page became a lifeline. And just when I felt I might hit bottom, a job offer came—a position as a computer programmer. It didn’t erase the pain, but it gave me something to hold onto. A thread of hope, just strong enough to pull me forward.

Blackwood & Marcia

“The true measure of success is how many times you can bounce back from failure” --Stephen Richards

After my split from Joyce in April 1988, I moved into a furnished apartment on the second floor of a home on Drexel Street in Blackwood, NJ. It had a private entrance, off-street parking, and was conveniently close to my new job at Business Operating Systems & Software—BOSS. The apartment was modest but charming, a quiet refuge during a time of emotional upheaval.

After my split from Joyce in April 1988, I moved into a furnished apartment on the second floor of a home on Drexel Street in Blackwood, NJ. It had a private entrance, off-street parking, and was conveniently close to my new job at Business Operating Systems & Software—BOSS. The apartment was modest but charming, a quiet refuge during a time of emotional upheaval.

For a two-room efficiency, it was surprisingly pleasant. The bedroom featured a cherry poster bed and matching dresser. The kitchen and living room formed a spacious area. The living room offered a compact sofa, a plush chair, end tables, and lamps. I added touches from my old home in Haddonfield, blending the past with the present.

In the kitchen, the stove and sink were cleverly tucked behind folding doors. A small table sat beside a window overlooking a backyard shaded by tall trees. Squirrels would sometimes perch on the sill, as if checking in on me.

I missed Joyce and the girls deeply. Their absence echoed through the quiet rooms. But my new role as a computer programmer helped ease the sadness. I found comfort in talking with Sandy Marmon, a colleague who had started at BOSS on the same day. She, too, was navigating life after divorce—hers overseen by my nemesis Judge Gaddos. We were assigned to the same project and quickly became confidants.

Sandy had graduated Cum Laude in computer science, and felt disillusioned by her career path. Eventually, she left BOSS to join Cigna as a Cobalt programmer. I stayed behind, but our friendship endured. We’d go out for dinner, catch a movie, or shoot pool. Since Sandy was twelve years younger, she kept our bond rooted in mutual respect and shared experience—not romance.

Occassionaly I’d visit her home on Saturday. She’d make breakfast, and I’d help her sons mow and trim the lawn. Her daughter, older and independent, kept to herself. Sometimes we’d take the boys fishing, those quiet outings offering a sense of family I still craved.

Wanting to dance again, in June I met Marcia at a nightclub where the music was loud, the lighting forgiving, and the conversation—somehow—easy. She was thirteen years younger than me, but age didn’t seem to matter. We connected quickly, and what began as a spark grew into something close and romantic.

She lived in a double-wide mobile home near Marlton, tucked among quiet roads and modest yards. Her companions were two elderly dogs, slow-moving and loyal, their eyes clouded with time. When the day came to say goodbye to them, Marcia didn’t hesitate. She adopted a greyhound from a rescue—a graceful creature with long limbs and a gentle soul. I’d never been drawn to large breeds, but this one won me over completely. To this day, it remains the only big dog I’d ever consider having.

Marcia was Jewish, and while I’d worked with Jewish engineers and families before, I’d never been part of their traditions. That changed with her. That year, I experienced my first Passover dinner—complete with matzo, wine, and stories that stretched back generations. I listened, learned, and felt quietly honored to be included.

The holidays took on new meaning. In searching for Hanukkah gifts, I managed to finish my Christmas shopping early—a small triumph, but one that felt like progress. It was a season of learning, of blending traditions, and of discovering that love often lives in the details: a shared meal, a thoughtful gift, a quiet walk with a dog who understood everything without saying a word.

Marcia and I didn’t last forever, but the years we shared left a deep mark. She taught me that grace isn’t always loud, that culture can be a bridge, and that sometimes the gentlest creatures—like a retired racing dog—can teach you the most about yourself.

Despite four years at BOSS, I never received a salary increase. I had developed two advanced inventory programs and a new General Ledger system that became part of the company’s proprietary offerings. I brought in four new clients and took over two more from departing staff. Still, when I requested a raise, they hired someone else to manage my latest client.

That was my cue. I began searching for fairer compensation and found it at Larmon Photo in Abington, PA.

Abington & Betty

“The only real battle in life is between hanging on and letting go” --Shannon L. Alder

My time in Haddonfield had begun to feel like a distant echo. After four years as a programmer at BOSS, I had built advanced software and secured new clients—yet fair compensation never came. In search of a better income, I found myself moving through three different companies in just 18 months, each transition carrying its own lessons and losses.

My time in Haddonfield had begun to feel like a distant echo. After four years as a programmer at BOSS, I had built advanced software and secured new clients—yet fair compensation never came. In search of a better income, I found myself moving through three different companies in just 18 months, each transition carrying its own lessons and losses.

The first stop was Larmon Photo in Abington, PA. The company’s president had developed Computyme® software, a robust system for point-of-sale, inventory, payroll, and receivables tailored to the photography industry. My work focused exclusively on Computyme®, written in PICK®, while the local police department relied on PRIME® software from the same company.

The commute from Blackwood, NJ to Abington wore on me, so I relocated to Pennsylvania. Jericho Manor, a brick apartment complex nestled in a wooded area, offered charm and convenience. I moved in on June 29, 1992. Furnishing the apartment from scratch, I chose a cherry wood bedroom set reminiscent of my previous home, assembled an armoire, and reupholstered a secondhand dining set from a neighbor. It was a modest space, but it felt like mine.

Marcia had helped me choose Jericho Manor, but soon after, something shifted. She began distancing herself, suggesting I find someone local to date. After four years together, her sudden withdrawal left me confused and hurt. We had never discussed marriage—perhaps she had hoped I would. Or perhaps my move felt like a quiet goodbye. Whatever the reason, she ended the relationship, and we never spoke again.

With no romantic prospects, I found solace in a friendly bar in Jenkintown, where I played pool and made new friends. That Christmas, I bought gifts for my pool hall companions—not out of obligation, but because in the quiet of my life, their presence had become something warm and real. Their appreciation cheered me in a special way.

At Larmon Photo, the rise of digital photography cast a shadow over the future. My payroll program may have been all they needed, and whispers of layoffs began to circulate. I knew it was time to move on.

Lightship Corporation in downtown Philadelphia offered a new beginning. They specialized in acquiring overdue receivables and used PRIME® software. My office on the 16th floor of Chestnut Street was bright and full of promise. Even more comforting was the unexpected reunion with Sandy Marmon—my old friend from BOSS—now working at Cigna’s Liberty Place just blocks away. We rekindled our friendship and shared lunch nearly every day for the next 15 years. Though romance was never in the cards, our bond was steady and meaningful.

In April 1993, I met Betty Stein at the Blue Bell Inn’s singles night. A woman at the bar declined my invitation to dance but introduced me to her friend Betty instead. Betty was graceful, warm, and we connected instantly. Soon we became a familiar pair—dancing on weekends, and earning smiles from regulars who saw us as a well-loved couple.

Friday nights were warm and familiar—dinners, dancing, The weekends weren’t dramatic or grand. They were something better—steady, grounding, and filled with the kind of companionship that doesn’t need to be explained. Just shared. Betty’s family lived nearby, and I was welcomed into their celebrations.

Betty lived in Lafayette Hills with her elegant cat, a regal creature with a plume of a tail and a personality to match. She’d dash home at the sound of the electric can opener, her loyalty as swift as her paws. Muffy loved to nap in the tree out front, perched like a queen surveying her domain. When I heard about a stray kitten in need of a home, I didn’t hesitate. I adopted her and named her Brandy. She was small, curious, and quickly became my quiet companion for the next 20 years, often perched on the windowsill, watching birds in the trees.

Betty’s home was a sanctuary tucked behind a row of Poplar trees, their tall trunks swaying gently in the breeze along a long cul-de-sac. At the heart was her Japanese garden—carefully curated, serene, and anchored by a rare Pygmy Maple whose crimson leaves shimmered like silk in the sunlight. A fence of bamboo separated her back yard from the neighbor’s, rustling softly like wind chimes when the air stirred.

The house itself opened onto a two-level deck that stretched from the dining room and kitchen, inviting slow meals and quiet conversations. I spent weekends at Betty's—raking, pruning, planting—my hands in the soil, my heart at ease. We shared meals on the deck, the scent of grilled steak mingling with the sweetness of country air. Sometimes we talked. Sometimes we didn’t. The silence between us was never empty; it was full of understanding, like the pause between notes in a well-played song.

Betty moved with intention. Whether arranging stones in the garden or setting the table for lunch, she brought a kind of quiet elegance to everything she touched. I found myself matching her pace, learning to appreciate the stillness, the subtle beauty of a well-placed fern or the way sunlight filtered through bamboo.

In May of 1994, Betty and I boarded the Song of Norway for a cruise through the Mediterranean—a voyage that would carry us from the canals of Venice to the sun-washed shores of Greece, from the rugged beauty of Sicily to the Renaissance charm of Florence, and onward to Villefranche and the vibrant streets of Barcelona.

At the time, I didn’t know the Song of Norway held a special place in maritime history. It was only later I learned it had been Royal Caribbean’s very first cruise ship—a pioneer of leisure at sea. But on that spring morning, it was simply our vessel, our floating home, and the beginning of something unforgettable.

Venice was a dream—gondolas gliding past stone bridges, the scent of espresso and salt air mingling in the breeze. Greece offered ruins and mythology, sun-drenched islands and olive groves. In Sicily, the land felt ancient, volcanic, and alive. Florence was a gallery turned city, every corner a brushstroke of genius. Villefranche shimmered with pastel buildings and quiet coves, and Barcelona pulsed with energy, color, and Gaudí’s wild imagination.

Onboard, Betty and I shared quiet breakfasts on the deck, watched the sea change color with the time of day, and danced under stars that seemed to follow us from port to port. We wandered cobbled streets hand in hand, tasted local wines, and let the rhythm of the Mediterranean carry us.

It wasn’t just a cruise—it was a passage. Through history, through beauty, and through the kind of companionship that deepens with every shared sunset.

Meanwhile, Lightship proved unstable. By September 1993, rumors of closure loomed. Just in time, I spotted an ad from the Philadelphia Housing Authority seeking a PICK® programmer. With five years of experience in both PICK® and PRIME®, I applied and was hired.

Chestnut Hill & Shanez

“When you can’t change the direction of the wind — adjust your sails” --H. Jackson Brown, Jr

I began work at PHA on September 17, 1993—my 53rd birthday. The job required residency in Philadelphia, and though I delayed the move for nearly two years, I chose Chestnut Hill—an affluent neighborhood known for its historic charm, boutique-lined streets, welcoming restaurants, and the Woodmere Art Museum. It felt like a place where life could settle into something peaceful, maybe even poetic.

I began work at PHA on September 17, 1993—my 53rd birthday. The job required residency in Philadelphia, and though I delayed the move for nearly two years, I chose Chestnut Hill—an affluent neighborhood known for its historic charm, boutique-lined streets, welcoming restaurants, and the Woodmere Art Museum. It felt like a place where life could settle into something peaceful, maybe even poetic.

I found a one-bedroom apartment in Chestnut Hill Village and moved in on June 30, 1995. Compared to my place in Abington, it offered more space and a sense of quiet elegance. The living and dining room windows overlooked a grassy courtyard, and the living room was large enough to accommodate a small, efficient office. I filled the dining room with a credenza of bookcases, artwork, memorabilia, and a pewter chandelier that held real candles—little touches that made the space feel like home.

The kitchen featured a tidy pass-through to the dining room, and the bedroom hallway held a walk-in storage closet. A built-in dressing table with a mirror sat outside the bathroom. It was a thoughtfully designed apartment, nestled in a neighborhood that bordered Wissahickon Park, where the winding trails and bubbling creek were beloved by artists and photographers, and the historic Valley Green Inn—built in 1850—stood as a quiet reminder of the carriage trade that once passed through.

My commute became simpler. The Chestnut Hill train station was just a short walk away, and I often spent my rides reading the Philadelphia Inquirer, jotting notes on global events, or composing Letters to the Editor. One of them was even published—a small but satisfying moment of recognition.

For a time, my son Joe lived with me at CHV. He had taken a job with the EPA in Philadelphia, and the commute from his home in Brigantine, New Jersey had become too much. Sharing the apartment with him was a joy. We rode the train together, swapped stories, and bonded over my coffee—Maxwell House Original. When he moved into his own place, he kept the tradition alive, telling friends his brew came from “an old family recipe.” That made me smile.

While living at CHV, I bought my third new Mitsubishi Galant. But one morning, as I headed to the train station, I found the car sitting on cement blocks—its shiny chrome wheels stolen. I was heartbroken. Still, aside from that incident, Brandy and I lived comfortably. She perched on the windowsill, watching birds in the trees, a quiet companion through the seasons.

Meanwhile, Betty and I had been together nearly five years. Our weekends were warm and familiar—dinners, dancing, sharing meals on the deck, or time with her family. But Betty wasn’t seeking permanence. She spoke often of her late husband, Bud, with a reverence that made it clear her heart still lived partly in the past. I was never permitted to call or visit during the week. Sundays ended promptly at 7:00 P.M., no matter how sweet the afternoon had been.

At first, I accepted the boundaries. I told myself that weekends were enough. But over time, the limitations began to weigh on me. I longed for more—for weekday dinners, spontaneous phone calls, the kind of closeness that doesn’t check the clock. I filled my evenings with writing, poured my thoughts into pages that no one read, and occasionally escaped to the pool hall for a game and a bit of laughter. Brandy curled beside me at night, her quiet purring a comfort, but not a cure.

On a quiet Tuesday night in January 1998, I found myself at the Blue Bell Inn alone. Betty and I had been going there less often, but the bartenders and regulars still greeted me like family. When asked, I simply said Betty preferred not to go out during the week. It was true, but it didn’t make the evening feel any less lonely.

While chatting at the bar, I noticed a woman on the dance floor—elegant, magnetic. Our eyes met, and something stirred. As the crowd thinned, she approached me and asked why I hadn’t invited her to dance “after our eyes met.” I explained I was in a relationship, but offered to share the final dance of the night. She accepted.

Her name was Shanez, and she was a phenomenal dancer. As the Blue Bell closed, I walked her to her car. She invited me inside and confided that she was married. Her husband played poker on Tuesday nights, which gave her space to dance. She suggested we meet again the following Tuesday, with one clear boundary: our relationship would be limited to dancing. I agreed.

And so began a season of Tuesday nights filled with music, movement, and laughter. We danced at venues across the region and earned a bit of local popularity. Shanez had a radiant sense of style and a charm that drew people in. She was so captivating that I invited my son Joe to come watch us dance. She was impressed by his gentlemanly grace, and in a twist of fate, played a role in introducing him to Patricia—who would become his wife in October 1999.

Shanez and I became close friends. She became a friend of my family, and I became a friend of her's. When she renovated her penthouse in Valley Forge, I helped with wallpapering and painting. Bob offered to install a hardwood floor over the terracotta tile in her living room. Unfortunately, once the subfloor was installed, we had to hire a friend familiar with flooring to install the hardwood and the money ran out, leaving us with no pay for the job.

In August 1999, I traveled to London with Shanez who was visiting her brother and his wife. Having lived in London before moving to the USA, she helped me find a well-located hotel. While she spent time with her brother, I explored the city, visiting landmarks like Big Ben, Buckingham Palace, and Tower Bridge.

I enjoyed typical London experiences such as fish and chips and pints of Guinness. I noticed that Londoners drive on the left, so you often need to "Look Right" before crossing streets. I also appreciated the unique language on signs, like "Way In," "Way out," and "Mind the gap."

Three years later, Shanez invited me to join her on a 10-day trip to Acapulco, Mexico. I was struck by the soft sand beaches and warm weather. We saw the famous La Quebrada Cliff Divers, who performed daring jumps into the ocean. On a tour inland, I learned about plantains. After trying one, I wouldn’t recommend eating them raw.

Despite careful precautions, I eventually caught "Montezuma's Revenge" and bought so much Pepto Bismol that the local store ran out. After that, I lost interest in returning to Mexico.

Shanez had two daughters, a doctor and a pharmacist. As her daughters married and her family grew, our dancing slowed. Shanez transitioned from hairdressing to holistic health and fitness, embracing a new chapter of her own. Eventually, our dancing came to an end, but our friendship endured—quietly, steadily—until I retired to Arizona.

Philadelphia & Anita

“You are never too old to set another goal or to dream a new dream” -- C.S. Lewis

Now that I had secured a stable job and a reasonable income, I set my sights on owning a home. Choosing a location proved difficult—until Shanez suggested the “Art Museum Area” of Philadelphia.

Now that I had secured a stable job and a reasonable income, I set my sights on owning a home. Choosing a location proved difficult—until Shanez suggested the “Art Museum Area” of Philadelphia.

Officially known as Fairmount, the neighborhood is named for the hill upon which the Philadelphia Art Museum stands. Its streets are lined with late 19th- and early 20th-century row houses, full of character and history.

I hadn't thought about living downtown but Betty still showed no interest in advancing our relationship beyond weekend visits and Fairmount offered so much more than charm.

It was alive with museums, fashionable restaurants, sidewalk cafés, and Fairmount Park, where the Schuylkill River flows past the iconic Boathouse Row, the Fairmount Waterworks, and the Art Museum. It felt like a place where life could unfold with excitement and pleasure.

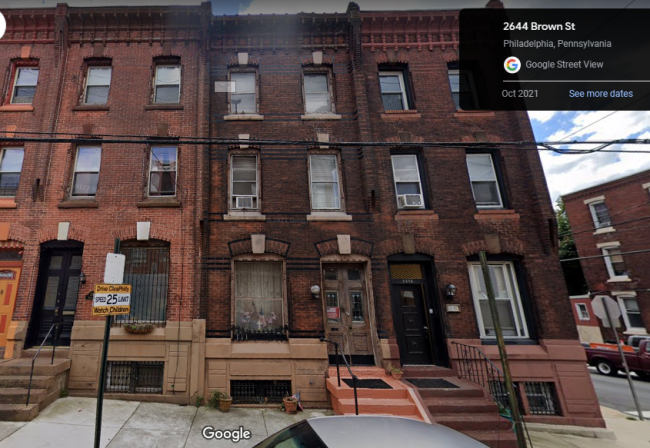

Taking Shanez’s advice, I began my search. My realtor introduced me to the idea of investing in a triplex, and in October 1998, I purchased a lovely corner property at 27th and Brown Streets and became a landlord. I didn’t know what the next chapter held, but I knew this was a place where stories could start.

The triplex was bright and cheerful, with windows on three sides. Each apartment featured an eat-in kitchen with glass-front cabinets, dishwashers, and garbage disposals. Ceiling fans spun quietly in the bedrooms and living rooms, and I installed air conditioning units to complete the comfort. The basement held a washer and dryer, storage closets, and a separate entrance on 27th Street.

I chose the first-floor apartment for myself. It needed work, but it had a 12-foot ceiling, a spacious kitchen, no stairs to climb, and a covered cement patio out back. The living room ceiling was stained, so I repainted it with popcorn paint. The windows and frames were worn, so I resurfaced and repaired them. Bit by bit, the space began to reflect my vision.

The foyer held a built-in bookcase, and I added a floor-to-ceiling mirror to open the space. The bathroom was in disrepair, but my son Robert stepped in—retiled the walls, replaced the floor, tub, sink, toilet, and fixtures. The transformation was stunning.

The bedroom was modest. The only closet was a built-in armoire in the hallway. Still, I made it work. Later, I installed two mirrored closets along the south wall with storage cabinets above, allowing me to remove the chest of drawers and replace it with a marble-top Bombay chest. It was a labor of love, but the result was a bright, elegant bedroom.

I hung a leaded glass chandelier that cast soft light over my dining table and painted the kitchen in two shades of green. I added a glass and wrought iron table set and placed my antique cedar trunk beneath the kitchen window. Every detail was chosen with care.

The second-floor apartment was a cozy one-bedroom with a den that could easily serve as a second bedroom. A charming little balcony extended off the living room, offering a quiet perch above the neighborhood bustle.

The third-floor unit was the crown jewel—spacious, bright, and inviting. Its entrance sat directly across the hall from the second-floor door, with stairs tucked neatly inside. It featured two separate bedrooms and a living room with a stunning view of the city skyline through a large rear window. On clear evenings, the lights of Philadelphia shimmered like a promise.

Of course, owning a corner building came with its own challenges—especially in winter. Snow shoveling was no small feat. I had to clear not only the front walk but also the long stretch of sidewalk along 27th Street. Still, the effort was worth it.

In January 2002, I purchased my second triplex on Brown Street. The price was reasonable, though the building needed a new roof, chimney repairs, and replacement windows in every room. Still, its location—just one door down from my first property—made it an ideal investment. I could manage both buildings with ease, and the proximity gave me a sense of quiet control over my little corner of Fairmount.

Like many middle rowhouses in the neighborhood, this one featured a narrow alley between buildings—hidden from the street but allowing for windows in every room. The apartments were more spacious than those in my first triplex, with generous kitchens. The stoves were apartment-sized, and there were no dishwashers, but the layout had charm.

The first-floor apartment had a unique layout. The living room faced the street, followed by a middle bedroom, then a kitchen tucked behind it. The bathroom sat at the rear, accessible through a narrow hallway that led to a brick patio in the backyard. It was quirky, but functional.

The second and third-floor units were both two-bedroom apartments with lovely hardwood floors. The second floor boasted a spacious eat-in kitchen and a full-size refrigerator. The third-floor stairway was narrow, so only an apartment-sized fridge could make the climb. Still, the unit offered two large bedrooms—one at the front, one at the back—making it ideal for roommates.

Both buildings ran on hot water oil heating, so I included heat in the rent while tenants covered gas and electric. The basement of the second building, however, was not useful—dark and often damp, with only two small front windows. To make up for it, I allowed tenants to use the laundry facilities in my other building, accessible through the outside entrance on 27th Street.

I knew moving to the city, my relationship with Betty would shift. But as I approached sixty, I longed for something deeper—a shared life, not just weekends. And Betty remained firm in her quiet devotion to the past, saying she was waiting to be reunited with her late husband, Bud. I respected her sentiment, but it left me standing alone at the threshold of something I had hoped would grow.

So I turned my energy toward building something of my own. I purchased property, and the demands of managing rentals gradually filled the time I once spent with Betty. It was a quiet pivot—from longing to purpose.

By now, Philadelphia had truly become my city. I lived there, worked there, played there. The value of my buildings had climbed to well over $1.75 million. I had built something solid—something lasting.

Shanez remained a constant in my life. We continued dancing, and she was thrilled about my new venture. On two occasions, we traveled together—once to London, once to Acapulco. In Acapulco, we even won a Salsa dance contest, twirling across the floor with ease and laughter. But our trips were never romantic. Just two friends, sharing joy in motion and discovery.

In the absence of a relationship, I decided to try online dating. In May 2001, I met three remarkable women—all teachers. One held a PhD and carried herself with elegance and charm, though she had a gentle stutter. Another lived in a condo along the Philadelphia waterfront, full of stories and warmth. But it was the woman from Doylestown who truly caught my attention.

Anita had a lovely home and a spirited Dachshund named Schnapps. We began dating, enjoying dinners out and occasional trips to New York City for theater—and even a bit of dancing, though Anita was shy about my enthusiasm. On Sundays, golf was always on the television. She asked why I never played and suggested her son could teach me. I accepted.

Anita had a lovely home and a spirited Dachshund named Schnapps. We began dating, enjoying dinners out and occasional trips to New York City for theater—and even a bit of dancing, though Anita was shy about my enthusiasm. On Sundays, golf was always on the television. She asked why I never played and suggested her son could teach me. I accepted.

Her home was near New Hope, a charming town nestled along the Delaware River. With its cobblestone streets, riverside cafés, and vibrant arts scene, it became a backdrop for many of our weekends. New Hope had a way of making time feel slower, more intentional.

Anita had friends from high school, including a couple who owned Tomara Farm—a historic property where visitors could step into the rhythms of colonial America. The main house was a museum of antiques and stories, and every Christmas season, it opened for tours led by guides dressed in period fashion. It was a tradition steeped in charm and reverence for the past.

In 2004, Anita and I joined a Baltic Sea cruise aboard the Ms. Noordam, traveling with a large group of her high school friends. It was my second time visiting the Baltic, but this trip included a flight to Moscow—a long-held dream. I stood in Red Square, gazed at the Kremlin, and felt the weight of history beneath my feet. It was unforgettable.

Meanwhile, in June 2002, I had played my first round of golf, encouraged by Anita. I quickly grew to love the game, and we played nearly every weekend, weather permitting, at nearby Fairways Golf Courtse.

Anita, a retired school teacher, worked part-time for a textbook company. She traveled often during the school year. Missing golf during Philadelphia’s cold winters, I started joining her on trips to warmer places with great golf courses.

Several trips took us to Mesa, Arizona, where the sun shines about 325 days a year. I enjoyed golfing there and thought it would be the perfect retirement spot. I pictured spending my days on the golf course, dining out, dancing on Friday nights, and grilling on Sundays.

When Anita’s son Bill decided to move his family to Arizona, it confirmed our plan to relocate too. Bill bought a lot in Fountain Hills and, as a construction engineer, planned to build a custom home. But we preferred Mesa for its charming downtown, closeness to Old Town Scottsdale and the Phoenix airport, and more affordable housing compared to other upscale areas.

In 2005, as housing prices rose in Arizona, Anita and I visited, staying at the famous San Marcos Golf Resort, one of Arizona’s original golf courses dating back to 1913. While there, we looked for a house. The closing date—05/05/05—felt auspicious, a little wink from fate.

©Copyright 2001 Charles Tyrrell - All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice