Sports

An Autobiography

Table Tennis

“Never underestimate the importance of having fun” - Randy Pausch

If it’s true that you play “Table Tennis” in an arena and “Ping Pong” in the basement, then I’ve had all of my games in the basement—but make no mistake, I play Table Tennis. The kind with spin, strategy, and a paddle that’s seen more action than a soap opera.

If it’s true that you play “Table Tennis” in an arena and “Ping Pong” in the basement, then I’ve had all of my games in the basement—but make no mistake, I play Table Tennis. The kind with spin, strategy, and a paddle that’s seen more action than a soap opera.

Back in high school at Sacred Heart, I was a table tennis champ. My serve had swagger, my returns had bite, and my reflex was quick. Fast forward a few decades—and a few thousand life experiences—and I found myself in senior living at Acoya Troon in Scottsdale, where someone casually mentioned table tennis as one of the activities. I was talked into picking up the paddle again. I thought, “This is going to be a disaster. My reflexes are probably in retirement too.”

Turns out, they weren’t.

We played twice a week, and within a few short rallies, I was giving Mac—the community’s reigning table tennis titan—a run for his money. Mac has since moved on, but I’ve stuck around, and while I haven’t inherited his “unbeatable” title, I’ve earned a new one: The Man. The Myth. The Ping Pong Legend.

The games are lively, the competition friendly, and the camaraderie delightfully vintage. Many of our residents were once tennis players, and a few have rediscovered their table tennis chops. Each week, someone watching from the sidelines gets that familiar itch, picks up a paddle, and joins the fun. Our little league has grown to five or six regulars, and the energy in the room is electric—well, as electric as it gets when half the players stretch before every serve.

Table tennis has become more than a pastime. It’s a weekly ritual, a social spark, and a reminder that some games never get old—they just get better with age.

English Darts

“English Darts is a professional competitive sport, played by 6 million people throughout the world”

My introduction to English Darts came in Centerville, Ohio, where I managed JCPenney’s Product Service Center. The neighboring business manufactured darts and, in an effort to promote English darts, the owner organized a weekly dart night at a popular local tavern.

My introduction to English Darts came in Centerville, Ohio, where I managed JCPenney’s Product Service Center. The neighboring business manufactured darts and, in an effort to promote English darts, the owner organized a weekly dart night at a popular local tavern.

Darts is a game with deep British roots, believed to have originated among soldiers who threw cut arrows or crossbow bolts at the bottoms of barrels for sport. Today, it’s a refined game of precision and strategy, where players take turns throwing three darts at a segmented board, aiming for high scores and tactical finishes.

The tavern’s dart night was quite a success. By pairing novice players with seasoned members of the local English Dart League, the owner created an atmosphere that was both competitive and inclusive. Novice players drew names from a hat, and suddenly strangers became teammates, sharing laughs, strategy tips, and an occasional celebratory toast.

A modest entry fee added just enough skin to the game. First and second place winners shared the pot, while third place walked away with a six-pack of beer courtesy of the bar—a prize that often came with more cheers than the cash. The tavern buzzed with energy, and game nights stretched into happy memories.

I was quickly swept into the rhythm of it all and became a regular participant. My skills improved rapidly, and I began winning matches alongside my league partners. Before long, I played as the experienced half of a novice pairing, eventually joining the English Dart League myself.

League matches were held weekly at sponsoring taverns, with home and away teams competing in classic English dart games like Cricket and 01. In the popular 01 game, players aim to reduce a fixed score—typically 301, 501, or 601—to exactly zero. The final dart must land in the outer double ring or the center bullseye to win. If a player overshoots, it’s a “bust,” and their score resets to the previous total.

The English dart game of Cricket involves only the numbers 20 through 15 and the bullseye. The objective is to score 3 darts in each of those numbers (closing the number) before the opponent does. The first player to "close" all the numbers wins.

In the tournament game of Cricket, a player can score points against their opponent by throwing darts into a number that the opponent has not "closed." The winner must be the first player to "close" all the numbers while also being ahead in points scored.

At season’s end of league play, trophies were awarded for team standings, best player, and most improved. I was honored to receive my first trophy for “Most Improved,” which encouraged me to enter several Ohio dart tournaments.

Though I never claimed a title, I reached the semi-finals in Columbus, Ohio and it was an opportunity to meet players from across the country—including a memorable character from Philadelphia known as “Tex,” who carried two sets of darts in holsters on his hips.

To start a game of darts, each participant throws a dart at the bullseye, and the player whose dart lands closest gets to go first. However, one memorable evening in Philadelphia, this usual procedure turned into a remarkable event. I had been transferred to New Jersey by JCPenney and decided to visit a tavern where Tex was known to play.

Tex was a a renowned tournament player celebrated for his style and accuracy, He stood at the oche—not facing the dartboard, but with his back turned. With a flick of his wrist, his dart hit the bullseye dead center. His opponent mirrored the throw, also hitting the bullseye, resulting in a tie.

They repeated the process. Another tie! Then a third time—the atmosphere in the tavern was electric. Spectators leaned forward as if watching magicians perform. It was more than just skill; it was sportsmanship, showmanship, and a kind of focus that seemed to defy reason. Tex’s third dart landed squarely in the center bullseye winning the toss.

I decided not to participate in the games that night. Instead, I watched quietly, taking in the display of expertise. It was a reminder that in darts, as in life, there are moments when talent goes beyond technique—when a simple throw becomes truly memorable.

After my transfer to New Jersey, I joined the team at Mt. Royal Inn in Mt. Royal, NJ. I held my own against top-tier players and was eventually elected president of the South Jersey English Dart League, a role I proudly held for six years. During my tenure, I introduced a structured handicap system to level the playing field for standings.

I designed a score sheet that tracked each player’s performance in triples, doubles, and out shots, allowing us to calculate fair handicaps. To streamline the process, I wrote a custom program and discreetly installed it on the JCPenney computer. After a night of league play, the secretary and I entered the data, printed the results, and mailed them to the teams the same evening—an efficient and appreciated innovation.

The English Dartboard itself is a marvel of design. Traditional boards are made from compressed sisal fibers, which separate cleanly when pierced by a dart, preserving the surface. The scoring area ranges from the central bullseye to the triple-score ring and the outer double-score ring.

The English Dartboard itself is a marvel of design. Traditional boards are made from compressed sisal fibers, which separate cleanly when pierced by a dart, preserving the surface. The scoring area ranges from the central bullseye to the triple-score ring and the outer double-score ring.

To count, a dart must land in a numbered segment. A dart in the inner triple ring (red and green) triples the score and a dart in the outer double ring doubles the score. The bullseye is configured with two concentric circles, Double-bull refers to the inner circle, which is commonly red and worth 50 points with the outer bullseye is worth 25 points.

American darts use wooden dartboards and wooden darts fletched with turkey feathers giving them a distinctive appearance and feel, unlike the tungsten or brass darts used in the British game. The scoring area of the board extends from the center bullseye to a red double-score ring and an uncolored triple-score ring, while the large outer blue ring is not part of the scoring area.

American darts, while rooted in the same spirit of precision and camaraderie as its British counterpart, has cultivated its own unique culture and competitive style. It has been popular in the United States for many years but differs significantly from the traditional game that originated in Britain.

The American dart game is Baseball. The baseball format adds a layer of strategy and storytelling to each match. Players progress through nine innings, aiming for numbered segments (1-9) in sequence. A well-placed dart in the triple ring can shift the momentum of a game, much like a three-run homer in a real ballpark. The scoring system is intuitive, yet demands consistency and control—qualities that seasoned players come to respect.

It's perhaps not surprising that American darts features Baseball, a traditional American bat-and-ball game played between two teams, while English darts features a game called Cricket, a traditional British bat-and-ball game played between two teams,

Darts has remained one of the most enjoyable and intellectually engaging games I’ve played. It combines focus, finesse, and camaraderie—and for me, it became a gateway to leadership, innovation, and lasting friendships.

Golf

“Once you learn how wrong golf can go you respect it a little bit more” --Curtis Thompson

I’ve always been a big fan of golf—Arnold Palmer’s swagger, Jack Nicklaus’s precision, Lee Trevino’s grin, and Greg Norman’s cool confidence. But for all my admiration, I didn’t swing a club until I was 62 years old. That’s right—while the golfers I knew had perfected their game in their youth, I was just learning the game.

I’ve always been a big fan of golf—Arnold Palmer’s swagger, Jack Nicklaus’s precision, Lee Trevino’s grin, and Greg Norman’s cool confidence. But for all my admiration, I didn’t swing a club until I was 62 years old. That’s right—while the golfers I knew had perfected their game in their youth, I was just learning the game.

As a teenager, I thought caddying sounded like a blast. My uncles golfed and I did caddy once—for my uncles—but I suspect my mother had other ideas. I carried their bags, worked up a sweat, and got paid with a hot dog and a Coke. Not exactly a PGA paycheck, but I suspected Mom orchestrated the whole thing to prove her point—golfers looked down on caddies as “poor kids.”

Fast forward to 1962. I overheard two coworkers planning a weekend round. One said, “I hope I break 100,” and I chuckled. He turned to me and said, “What? You think we play like those guys on TV?” Honestly, I did. I thought every golfer was born with a perfect swing and a country club membership.

Later, I told that story to a lady friend, and she offered a solution: her son Bill would take me out on the course. She didn’t golf herself, but she took me to a driving range and showed me how to stand and hold the club. I swung. I hit the ball. I was hooked.

Bill agreed to teach me the game, and I bought a set of used clubs and a shiny new Ping putter. Looking back, I was a terrible golfer. Once on the first tee, I hit the ball straight up into the air—it ricocheted off a tree branch and nearly took out the starter. Not exactly textbook form.

Still, I loved the game. After every bad shot, I believed the next one would be better. And sometimes, it was. The hardest part? Stringing two good shots together. But I kept at it.

Eventually, I upgraded to a new set of Wilson clubs and started taking lessons. One day, I apologized to my instructor for my bargain gear. He pulled out my three-wood, smacked the ball 250 yards, handed it back, and said, “This one works.” Lesson learned: it’s not the club—it’s the swing.

Anita gifted me a set of Cleveland irons for my birthday, fitted to my swing. They felt like magic. I added Cobra woods with flexible graphite shafts, and for the next 17 years, that combo was my trusty arsenal. The one club I’ve never replaced? My Ping blade putter.

Anita and I played almost every weekend at Fairways Golf Course. I also teed off with Sharon and Kevin, Shanez and Eric, and played beautiful courses like Shannondell and Five Ponds. After retiring, Sharon and I hit Westover Country Club during the week. When no one was free, I’d play Walnut Lane—a narrow municipal course that taught me how to keep the ball straight, even if it didn’t go far.

Anita and I played almost every weekend at Fairways Golf Course. I also teed off with Sharon and Kevin, Shanez and Eric, and played beautiful courses like Shannondell and Five Ponds. After retiring, Sharon and I hit Westover Country Club during the week. When no one was free, I’d play Walnut Lane—a narrow municipal course that taught me how to keep the ball straight, even if it didn’t go far.

Philadelphia winters were brutal for a golf lover. So I tagged along with Anita on her business trips to Florida, Nevada, and Arizona. Florida was nice, Vegas was a blast, but Arizona? That was love at first tee.

After several trips, I knew Arizona was where I wanted to retire. Anita’s son Bill beat us to it, buying a lot to build a custom home in Fountain Hills. Anita and I found a gem in Mesa and settled on it—fittingly—on Cinco de Mayo, 05/05/05. I joined Red Mountain Ranch Country Club, but the dream fizzled.

In July 2007, Anita and I moved into our Mesa home. But things unraveled. She stopped golfing, Brandy the cat was exiled to a closet. Bill and Hanna moved elsewhere. I was left with an $8,700 membership and $450 monthly dues for a game no one else was playing.

By January, I knew I couldn’t stay. I moved into a condo on Recker Road and kept golfing with my buddy John. On May 30, 2008, I scored a hole-in-one on hole 4 with him at Red Mountain. A perfect shot from 153 yards and a perfect day.

Still, I missed my Pennsylvania golf friends. So I went online, searching for someone who “liked to golf and dance.” That’s when I met Joan.

Joan lived in Anthem, AZ, home to two stunning courses—Persimmon and Ironwood. She’d given up her golf membership, but after dating a while, she spent weekends with me, and we played many rounds together at Red Mountain. Eventually, we moved in together and rejoined Anthem Country Club.

Joan returned to the ladies’ 9-hole league, and I joined the men’s Monday league. Those guys could drive a ball like it owed them money. I was intimidated, and my high handicap only helped when I had a miracle round. So I stuck to playing with friends and Joan.

When the courses got too tough, we gave up our membership and found joy at Sun City courses like Palmbrook and Union Hills. For five years, Marvin, Nate, Allen, and I played the pristine Wickenburg Ranch, with Hank occasionally subbing in.

I never became a great golfer. My best game was an 86, and I usually hovered in the 90s. I didn’t hit long, but I hit straight—thanks to Walnut Lane’s narrow fairways and years of stubborn practice.

Today, Joan and I have hung up our golf shoes. But Acoya has a golf simulator we enjoy whenever the mood strikes. And while our golf game may have mellowed, our dancing hasn’t. On the dance floor, we’re still pros—twirling, dipping, and gliding like we’re chasing a trophy.

Shooting

“I could no longer hold a rifle steady so I began shooting pistols”

Some individuals oppose firearms, yet there are numerous myths and misunderstandings surrounding guns and gun ownership. I may begin by stating my qualifications for discussing this topic.

Some individuals oppose firearms, yet there are numerous myths and misunderstandings surrounding guns and gun ownership. I may begin by stating my qualifications for discussing this topic.

I hold an Arizona Concealed Carry Permit, own three distinct handguns, and belong to the Scottsdale Gun Club. While a permit isn't required in Arizona, it shows that I have been trained on the legalities and responsibilities associated with owning and carrying a firearm.

Carrying and firing a gun is not like what is depicted in films. A loaded 9mm pistol weighs approximately 2 pounds, the weight of a quart of milk. That's a heavy object to stick in your belt or to carry in a pocket. Additionally, it requires technic and considerable strength to load a magazine and "rack the slide" to arm a 9mm pistol.

A loaded firearm cannot "go off" simply by being dropped or thrown, unless it has been damaged in some manner. For a gun to pose a danger, it must be loaded, aimed, and the trigger pulled. This is why responsible gun owners strictly adhere to these fundamental rules of gun safety.

- Always assume every gun is loaded

- Never point a gun at anything you wouldn't want to destroy

- Never put your finger on the trigger until you intend to shoot

My personal opinion on protecting the second amendment is that our fore-fathers had the fore-sight to know that we could vote our way into an oppreesive government but we would have to shoot our way out of it. Examples of oppressive governments and no way out can be witnessed throughout history.

In the past, reloading a pistol and a rifle was necessary after each shot. The invention of the revolver in 1791 allowed for multiple shots without reloading. Subsequently, rifles were developed in a similar manner, leading to the classification of these firearms as semi-automatic weapons.

Semi-automatic weapons fire one round each time the trigger is pulled. Fully automatic weapons can fire multiple rounds of ammunition with a single pull of the trigger. The challenge in enacting sensible gun laws is that gun-control advocates usually confuse or ignore what defines an assault weapon.

The AR-15 is a semi-automatic weapon that requires pulling the trigger for each shot. Since it is a widely used firearm in mass shootings, it has been incorrectly labeled as an assault rifle, but the AR-15 is produced by Armalite, with the AR standing for "Armalite Rifle," not Assault Rifle.

Almost every major gunmaker produces its own version of the AR-15 and 16 million Americans own at least one. If shootings were a gun problem and not a people problem, it would be obvious.

There are approximately 300 federal laws and regulations concerning firearms. Moreover, individual states implement additional gun laws and in every state it is illegal to sell or transfer a gun without a background check, even at a gun show.

Generally, gun laws cover background checks, certain typss of firearms, age restrictions, banned persons, permits, open carry, concealed carry, displaying, brandishing, and discharging a weapon. It is always unwise to bring a gun into any state without first reviewing that state's specific gun regulations.

In 1994 the Fedeeral Assault Weapons Ban (FAWB) was enacted. When it expired in 2004, it was not renewed because the majority of homicides were committed with firearms not included in the FAWB. Furthermore, the assertion that the FAWB decreased fatalities and injuries from mass shootings was inaccurate, as the semi-automatic weapons commonly used in those incidents are not "assault weapons."

Owning a gun carrys responsibility. But responsibility cannot be legislated. During my time in the military, we were taught that our rifle was our best friend. We learned how to properly handle and respect our rifles. I could "break it down" and reassemble it in the dark. I enjoyed shooting and was regarded as a very good shot—not a Marksman, but still quite capable.

My brother and I owned Daisy BB guns when we were kids and set up a shooting gallery in our basement. It was made up of two wooden shelves where we set up small rubber cowboys and Indians. Although BB guns posed little danger, we learned to shoot accurately and to respect the guns. We practiced 'shooting from the hip.' and used an old quilt placed behind our gallery to catch the BBs, allowing us to reuse them.

I take pleasure in target shooting, but not in hunting. I once shot an arrow at a bird in its nest. The arrow missed the bird but ended up covered in egg yolk. The thought of destroying the bird's eggs was troubling enough but after I shot an opossum with a .22 rifle but watching the poor animal die in pain it didn't undertand, ended my hunting days for good.

At my current age, a rifle feels too heavy to hold steadily. However, I enjoy shooting pistols. I own three distinct pistols: a 9mm semi-automatic, a snub-nose .357 Magnum revolver, and a .22 western revolver that I equiped with a pearl handle for fun.

At my current age, a rifle feels too heavy to hold steadily. However, I enjoy shooting pistols. I own three distinct pistols: a 9mm semi-automatic, a snub-nose .357 Magnum revolver, and a .22 western revolver that I equiped with a pearl handle for fun.

My 9mm is a stylish CZ P10C, a prized model valued at $800. The slide has been customized, and the trigger has been slightly modified by Cajun Gunworks. The P10C is comparable to the popular Glock 19 but, for me, it offers a more comfortable grip, night sights, and exceptional accuracy.

My .357 Magnum is a snub-nose Ruger LCRx revolver that can also fire .38 Specials. The LCRx is lightweight and easy to carry, though it isn't particularly enjoyable for target shooting. The short barrel makes the recoil more uncomfortable, especially when firing Magnums.

The .22 revolver is a Ruger 22LR Single-Action Revolver. Its long 4.5" barrel makes it ideal for target shooting. It holds six rounds and loads just like the classic western six-shooters.

Although I hoped never to need it, I typically carried my 9mm or my .38 but always in a holster. Holsters are designed to prevent access to the trigger until the firearm is removed from the holster.

While I usually carried my gun in an outside the waistband (OWB) holster, it was always concealed. Open carry can be risky; in a criminal situation, someone spotting your gun could make you the primary target.

An interesting point of concern regarding gun ownership and gun-control advocates is that, while they deny any intention to confiscate firearms, they might attempt to impose taxes on guns and ammunition to the point of making them unaffordable.

Camping & Canoeing

“The rapids swept us under a tree that had fallen out over the river”

One of the highlights of my life were the weekends Bob, Joe and I went off for a weekend of camping, fishing and canoeing. Mostly, our camping trips were an annual event centered around Father's Day. They were great trips that ended with fresh fish cooked over an open fire by chef Robert and evenings by the camp fire with a beer.

One of the highlights of my life were the weekends Bob, Joe and I went off for a weekend of camping, fishing and canoeing. Mostly, our camping trips were an annual event centered around Father's Day. They were great trips that ended with fresh fish cooked over an open fire by chef Robert and evenings by the camp fire with a beer.

One of our best outings was to the Delaware Water Gap in Pennsylvania. My dad had taught me canoeing skills and they came in pretty handy when low water levels along the Delaware River had created some tricky passages and rough rapids.

On one outing, the rapids were pushing us to the left bank where a fallen tree was stretched out over the water. I was struggling to keep control but yelled out to "lay flat" just as the strong currents swept our canoe under the tree. I lost my hat to the tree but, thankfully, that was the only damage.

If you've ever been camping when it rains you would really appreciate Bob's knowledge of the outdoors. He would bring a huge tarp that we would hang up over a flat, clear area and positioned our tents under the tarp. It kept the ground around our tents nice and dry when it rained.

Bob loved fishing. He was always right at home in the middle of the woods next to a trout stream. Well, actually any stream, river, pond or lake. He always managed to catch enough fish for dinner. In addition to his fishing skills, he had the skill of cooking over an open fire and he had the recipes to go along with his in-the-woods cooking.

When the boys were young, we often joined Arlene's parents on their annual camping trip to Fish Creek Pond in the Adirondack Mountains. I think Bob inherited his fishing skills from his grandmother. She loved fishing and sometimes brought home a bucket of Bullheads for dinner that she caught in the St. Lawrence River in Massena.

Camping at Fish Creek was a great experience for the boys. The camp sites had sandy beaches so they could swim and fish. Their grandfather had a boat so we always got a camp site with a dock. We used the boat for fishing and to explore the passageways winding between Fish Creek Lake and Upper Saranac Lake.

We often took the boat down to the marina for food and supplies since it was shorter than driving around the lake. One fateful day we lost the drain plug. Keith had to jump off the boat at the marina and buy a plug while I kept the boat moving. After circling a few times, I stopped just long enough for him to get back on the boat with a new plug.

Canoeing was also popular. Keith and his wife, Arlene and I had taken canoes down the lake for a picnic in the woods when a storm came up. This happens often in the mountains. This day, however, there were white-caps on the lake, Arlene got sick and could not help paddle. We eventually made it safely back to the camp site but Keith and I both learned that when you take a woman canoeing be prepared to do all the paddling.

Skiing

“When snowboarding began taking over the ski slopes, I quit skiing”

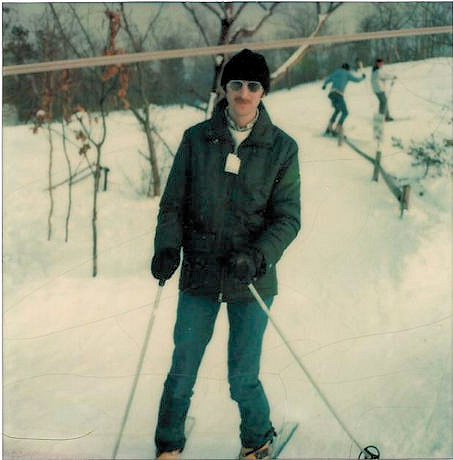

Barbara was an avid skier who grew up in Vermont. I had never been on skis but we had been dating for a while and she thought I would enjoy the sport.

Barbara was an avid skier who grew up in Vermont. I had never been on skis but we had been dating for a while and she thought I would enjoy the sport.

We went to Ski Mountain in Pine Hill, NJ and I took lessons. Barbara was familiar with the South Jersey Ski Club and they offered some fun adventures. The club would leave by bus on Friday night headed for a great ski destination and return on Sunday night.

We decided it would be best to join the club. I did not have any ski equipment and it was fun shopping for skis, poles and boots. An unspoken rule in skiing is that everyone carries their own equipment"

My first season of skiing I did quite well. We had some very fun and exciting trips to Vermont, New York, New Hampshire and even New Jersey. One of my favorite places to ski was Killington in Vermont.

I suffer from acrophobia but skiing never bothered me as long as I looked straight ahead on the ski lifts. The perspective when going uphill made it appear I was closer to the ground than I was. The view behind was usually awesome but I could seldom turn around to enjoy it.

Only once did my acrophobia become a problem and it was quite embarrassing. On a trip to New Hampshire, the top of the mountain provided a view of four states. I was busy snapping pictures and didn't realize how quickly the trails dropped off. Suddenly my acrophobia kicked in and I lost control my legs.

I helplessly looked around realizing that the best I could do was lock my legs into a "snow plow" position. Snow plowing is ski lesson #1 and works best on a gradual slope. Finally, I saw a trail marked "scenic route" and decided it was my safest option.

It would have been ideal except that rounding the first bend on the scenic route I had a cliff on one side protected only by a split-rail fence. With my heart pounding and my legs like jelly, I somehow made it down to the main trail. I stood there for a while to calm down and regain my equilibrium.

By now my companions were on their second trip down the mountain and were looking for me. I explained what happened and assured them I was okay. I took a deep breath and followed them down the mountain. On our next trip up the mountain, at the top I jumped off the lift and just hit the trail.

One season the ski club was going to Whiteface Mountain near Lake Placid, NY. My sons lived in nearby Massena, NY and I thought it would be fun if they joined me for a weekend of skiing and camaraderie. I made all the arrangements and we had a wonderful weekend together in spite of their mother's efforts to turn it into a disaster.

The funniest incident I remember was the time Barbara forgot to get off the ski lift. First of all, getting on the lift I clumsily knocked my hat off. The couple behind us grabbed it off the ground. Barbara and I were chatting all the way up and at the top of the mountain Barbara didn't get off the ski lift.

When that happens, your feet trip a safety wire that shuts down the lift. I don't remember how they got her off but a ladder was involved. When the lift started again, the couple behind us handed me my hat and quickly left as if to say "We're getting out of the way of these two klutzes."

And speaking of klutzes, there is another story of Whiteface Mountain. Whiteface is one of the highest mountains in New York State so we spent the first day or so getting off the lift half-way up the mountain. When we finally decided to go to the top, I lost my ski poles to a real blunder.

On the way up the mountain, I hung my ski poles on the chair's safety bar and put my hands in my jacket to keep them warm. As we approached the half-way point the lift attendant seemed to be agitated, jumping up and down and waving her arms. Suddenly I realized my ski poles were hanging below the chair.

In my panic, I couldn't get them off the bar in time and as we crossed the unloading ramp my poles were bent in half. Just as I suspected, when I tried to straighten them out at the top of the mountain, they broke. I didn't want to leave broken poles on the mountain so I skied down the mountain holding four halves in my hand.

One of the most fun trips was to the Playboy Club in New Jersey. It was a public ski resort run by the Playboy club and we went more for the experience of the club than for skiing. And an experience it was.

After a day of skiing, we found the room and service outstanding. The "bunnies" were charming, polite, attentive and pretty. Their outfits were actually quite adorable with the French cuffs and the little bunny tail.

The evening ended with a great dinner in the well-appointed dining room and Barbara and I opened the first night of entertainment with our dancing. In the morning at breakfast several people approached our table to tell us how much they enjoyed our dancing.

Barbara was a great dancer and our choreography often earned us the reputation of the most impressive couple on the dance floor. On the second night, as the band began to play for the evening's entertainment, they announced, "Okay, where are our dancers Barbara and Charlie?" We obliged.

Tennis

“Too clumsy for high school basketball, I took up tennis”

In high school, standing six-foot-one, I was a walking expectation. Coaches saw height and assumed basketball. I could sink shots from far out—what would later be called the three-point line—but back then, those long-range baskets earned no extra glory. Still, I had the touch. What I didn’t have was the grace.

In high school, standing six-foot-one, I was a walking expectation. Coaches saw height and assumed basketball. I could sink shots from far out—what would later be called the three-point line—but back then, those long-range baskets earned no extra glory. Still, I had the touch. What I didn’t have was the grace.

Basketball wasn’t my game. I was always “walking” or “fouling.” If I bumped someone, it was my foul. If they bumped me, it was still my foul. The whistle seemed to follow me like a shadow. I would have spent more time on the bench than the scoreboard.

Volleyball was kinder. I could jump, and my long reach made me a force at the net. There was something satisfying about timing a block just right, the ball ricocheting off my hands like a punctuation mark. It felt like I belonged there—at least for a while.

Baseball was another story. I had a cannon for an arm, but catching and hitting were mysteries. The truth came out with the arrival of 3-D comic books. Everyone else saw superheroes leaping off the page. I saw… nothing. Turns out I had one weak eye and no depth perception. That explained a lot. You can’t hit what you can’t see in three dimensions.

Football held promise. I could catch a pass and outrun most of the guys on the field. But I was “too skinny,” they said. Not built for the bruises. Still, I found a way in—I worked the field down marker and chain. I wasn’t in the huddle, but I was part of the rhythm, moving with the game, measuring its progress yard by yard.

Then came tennis.

No one expected much from tennis. The jocks called it a “sissy sport.” There were no two-handed backhands, no grunting theatrics. Just quiet focus, footwork, and timing. I loved it. I played for forty years.

My brother and I shared the court often, trading shots and stories. Later, he developed tennis elbow and had to stop. But my sons, Bob and Joe, picked up the game. We played together, laughing, competing, connecting. The court became a place of continuity—a thread that ran through decades of change.

I didn’t find my game in the swish of a basket or the clash of helmets. I found it in the quiet bounce of a tennis ball, the arc of a serve, the shared joy of a rally. And in that rhythm, I found something better than victory—I found belonging.

Baseball Fan Club

“The days of peanuts and cracker jacks had disappeared”

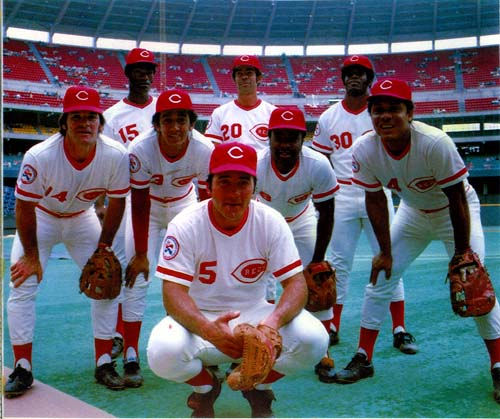

The Cincinnati Reds baseball team dominated the National League from 1970 to 1976 winning five National League Western Division titles, four National League pennants, and two World Series titles. The team's combined record from 1970 to 1976 was 683 wins and 443 losses. It is recognized as among the best in baseball history.

The Cincinnati Reds baseball team dominated the National League from 1970 to 1976 winning five National League Western Division titles, four National League pennants, and two World Series titles. The team's combined record from 1970 to 1976 was 683 wins and 443 losses. It is recognized as among the best in baseball history.

I was always a Cincinnati Reds fan and a Pete Rose fan. During all the years I spent in the Philadelphia area, I became a Phillies fan, especially after Pete Rose transferred to the Phillies.

Between 1980 and 1983 legends like Tug McGraw, Steve Carlton, Mike Schmidt, and Pete Rose led the Philadelphia Phillies to win two pennants and a World Series. They might have won another world championship in the 1981 season but they were unable to regain their winning ways after the sixty-day players' strike.

There was a time I enjoyed going to a baseball game. When we lived in Centerville, near Dayton, I took the boys to see the Big Red Machine. But times were changing. The days of peanuts and cracker jacks had disappeared and even the price of a hot dog and beer cost more than tickets in the bleachers. After baseball banned Pete Rose and then went on strike for an entire season, I lost interest in attending the games.

After moving to Arizona, I never became a Diamondbacks fan. I discovered that once you stop following a sport long enough that you don't know the players, the thrill of watching the games is over.

©Copyright 2001 Charles Tyrrell - All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the author. Copyright Notice